“Ah, shit! I’ve broken my leg…”

Two Bolivian ladies flutter anxiously around me as I attempt to get up from the pavement, my spectacular stumble-and-fall still fresh in my memory. My leg is askew in front of me, battered and bruised. The knee joint has separated completely from the calf; the two halves lie a significant distance from each other.

Just as well it’s a prosthetic leg, really.

But I feel much worse about breaking this artificial limb than I do about the huge scrape on my own knee – although limping onwards to the clinic is certainly a tad painful.

Will Jorge be able to put the prosthetic back together? Or have I cost him a significant amount of work?

For the last few weeks, I’ve been volunteering at an artificial limb clinic in La Paz.

To date, it’s probably the strangest volunteer project I’ve ever taken part in, and the most removed from any skill set I possess – but after working with children and teaching English all over the world, I thought it was time to change things up a bit.

The artificial limb clinic in question is Centro de Miembros Artificiales, a not-for-profit organisation based in Bolivia’s pseudo-capital, La Paz. It used to run just once a year, around Christmas time, until a volunteer from America, named Matt, came to visit. He recognised the importance of the clinic’s work, and made it his personal goal to find a long-term building to for the clinic to use, and keep it open year round.

Now, thanks to the donations primarily organised by Matt himself, the small group of staff (and the regular influx of international volunteers) keep the clinic running, and provide artificial limbs, almost always free of charge, to Bolivian amputees who have no other way of receiving a limb.

Read more: My Ultimate Travel Guide to Backpacking Bolivia

My first encounter with artificial legs

At the moment, the clinic is dealing specifically with patients who need artificial legs – the kind of limb that, in a usual setting, would cost anywhere from $3,000 to $5,000. And for people living in one of the poorest countries in South America, this is a sum that’s phenomenally difficult to get hold of.

A lot of the patients at the clinic have either made do with homemade limbs for years – limbs made from wood, cardboard and metal, that cause pain and don’t support their bodies correctly – or they’ve simply learnt to cope without a leg instead.

Thankfully, due to the efforts of Jorge and Florencio in the workshops and Ivonne overseeing proceedings, the clinic has managed to provide almost 150 Bolivians with new legs over the last few years, and hopefully this number will only continue to grow.

When I arrived at Centro de Miembros Artificiales in La Paz though, things were in a state of temporary paralysis. An unforeseen issue had arisen, and the clinic suddenly needed to move locations.

You’d think this wouldn’t be the biggest of issues, right? But you’d be wrong – particularly when you remember that this is Bolivia, a country that prescribes to South America’s supremely casual attitude to ‘getting things done on time’.

Moving the clinic isn’t just about switching buildings. It involves packing up the old place (dismantling machines, sorting through cupboards filled with documents, and clearing two years worth of excess plaster from the workshops), and starting all over again in a new set of rooms. Bare, empty, and devoid of patients.

Read more: Five things to know before travelling to Bolivia

I found myself unexpectedly in a state of transit by dint of this moving process, even while I’d designated La Paz as the place I’d settle down for a few weeks. And even as it was being dismantled and put back together again, I realised I knew virtually nothing about the clinic itself.

So while I was organising the filing cabinet of patient folders one day, I took the chance to get to know these artificial limb candidates a little better. On paper, at least.

“How was the patient’s leg lost?”

They are food vendors, bus drivers, pro fighters, students, locksmiths and street sellers. They are young men and old women, teenage girls and grandfathers, who live in the city and nearby towns and far off places in the countryside. They come alone, with family, or with friends; but regardless of their state, every single person tells their story to someone at the clinic.

I read through pages of short, concise paragraphs, each one describing a unique experience of pain and difficulty that led to the loss of a leg. A car crash; prolonged suffering of diabetes; an unexpected train running over a leg; an electric shock; stepping on a broken nail and contracting blood poisoning; an accident at work; a history of falling, which eventually alerted doctors to bone cancer.

With so many of the stories, there’s a common thread: the medical care these patients received in the past was woefully lacking. I read multiple reports of doctors with confused priorities; some perform immediate amputations before exploring other potential solutions, while others delay limb-saving treatments because strikes and transport issues prevent them from coming to work.

Still more have avoided treating a patient’s wounds altogether because said patient was comatose – “and they couldn’t be bothered to waste their time with me if I was never going to wake up”.

Many of the clinic’s patients state that they woke up from an accident to discover a missing leg – meaning the doctors sometimes don’t even ask permission from the patient before operating. It began to dawn on me that a huge amount of Bolivian amputees hadn’t needed to lose their legs in the first place – but the actions of some over-eager doctors result in life long difficulties, and necessary adaptation to an even harsher living environment.

“How has limb loss affected the patient’s life?”

The vast majority of the clinic’s patients say they’ve felt discriminated, shunned, and ultimately like a burden to their families and friends as a result of losing a leg. Suddenly unable to perform the simplest of tasks, usually losing their employment and independence, and sometimes also losing the support of their loved ones is a huge blow to their confidence.

Many patients even say they’ve thought about ending their lives before they became “completely useless”.

I have no doubt that every one of us would put equal value on having a fully operational body – but here in Bolivia, I get the impression that loss of a limb has the ability to put a stop to any semblance of a normal life.

The cost of medical bills are enough to split a family apart, not to mention the price of a new leg. I read the story of a man who needs a connecting part for his artificial leg, which will cost 800 Bolivianos (£80). It’s a huge expense for Bolivians, yet luckily the man’s children have volunteered to work and pay for the cost.

“What will change for the patient as a result of receiving a new limb?”

When many patients learn about the clinic, they realise it’s their chance for something life changing. The excitement is evident just from short paragraph descriptions.

“During his first visit to the clinic, he was kissing everyone, kissing Matt, kissing Ivonne. He was motivated to turn his life around and regain the respect of everyone in his life. He worked very hard to build up his strength. His goal was to ride a bike again.”

The desires of patients range from the simplest of wishes to the biggest. Some want to accomplish personal goals they never thought they’d manage again – like the woman whose face lit up as she explained the simple things she would be able to do on her own again, like cooking breakfast, washing dishes, and doing the laundry.

Others strive for different goals: like the man who had an accident when driving a bus, only to find the bus company refused to employ him again after his resulting amputation. One of his great motivations for exercising and strengthening his body was so he could proudly walk back into the terminal and show everyone he came out of the accident triumphant.

But reaching these goals is hugely dependent on the patient’s age, health and their dedication to coping with a new kind of difficulty.

And what isn’t documented so well in the patient files is the hours of painful practice as the patients get used to their new limbs. The constant stumbles and falls, the confusion at not knowing how to walk correctly, the realisation that they have to learn to walk again, from scratch.

Because using a prosthetic isn’t the same as having your old leg back.

Consultations at the artificial limb clinic

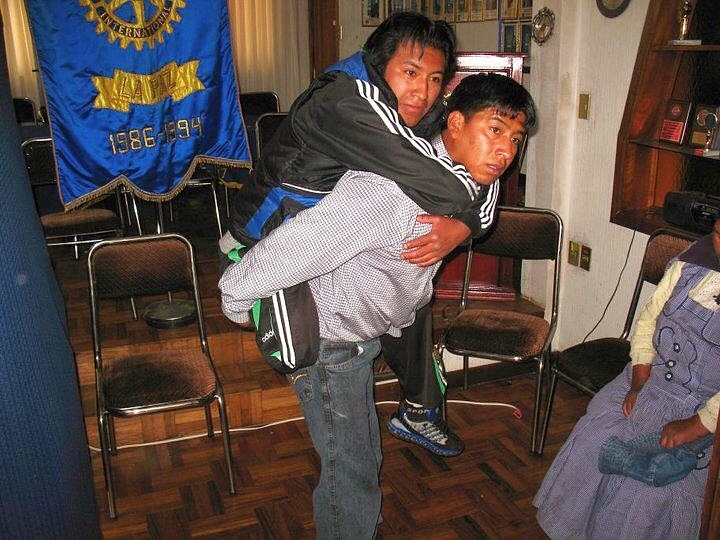

My time at the clinic wasn’t exclusively moving boxes and organising folders, though. During my first week, we were still welcoming previous patients to the clinic for physiotherapy and final fittings, so I was able to meet a few of them and see firsthand how they deal with their prosthetics.

I watched middle aged men stand between two metal bars, eager as children, constantly asking if they could start trying to walk yet. I watched the temporary physiotherapist, an English volunteer, swivel their hips and tap at artificial knees in an attempt to make them understand the right walking technique.

And I watched an elderly farmer take his first stumbling steps with his new leg, brought to the clinic only because an Australian guide on the Death Road biking route happened to see the man begging a number of times during his tours, and thought he’d find out why.

Sometimes the clinic has to face insurmountable difficulties, though. I watched one man’s face fall when he was told he couldn’t be provided with an artificial leg, because the clinic staff felt that, at eighty years old and living by himself in a place without a bathroom, he’s ultimately safer using the cane he already walks with.

Safety consciousness should always prevail, certainly, but it doesn’t make the outcome any easier to hear.

Then there was the cholita beggar woman, who only spoke to us in Aymara and was at the clinic for the third time in a matter of months because she needed her artificial leg changed. Ivonne, who runs the clinic, whispered to me that the woman has nowhere to wash, so the leg gets dirty extremely quickly and her stump gets infected.

A problem so simple, and so clearly prevalent in Bolivia – but one that had never even occurred to me.

What did I learn from working at Centro de Miembros Artificiales?

My time at the artificial limb clinic wasn’t what I expected. The hands on experience with patients that I’d hoped for was sidelined, and instead I spent most of the month learning the history of the clinic, and about the work they do there.

But maybe that’s ok. Things often don’t go to plan, and it was wonderful to spend time with the people I was able to meet. Besides, I don’t honestly know if I possess the skills to build new legs and feet out of metal and plaster in a workshop environment anyway!

If my trip, fall and subsequent leg break in the street is anything to go by, I’m probably better off being responsible solely for my own legs, and not other people’s.

Centro de Miembros Artificiales is an incredible place, doing hugely important work and helping Bolivians in a way that not many others are willing to do. And I’d like to think that if I ever end up back in La Paz again, there’ll be a more-than-worthwhile project for me to volunteer at once again.

And the next time, I’ll be properly prepared for every limb I’m tasked to look after. Both my own real ones, and the artificial kind.

Pin this article if you enjoyed it!

If you’re travelling to La Paz and would like to help out at the clinic, you can get in touch at www.FunProbo.com and follow their journey on their Facebook page.

8 Comments

Ann

October 25, 2013 at 1:17 amA very interesting article, with great images!

I really enjoyed reading this.

Ann from Australia

Flora

October 26, 2013 at 4:52 pmThanks Anne, I’m glad you enjoyed it!

Amanda

October 25, 2013 at 10:02 amWow. This was an amazing article and very interesting. It really makes you stop and think about we often take for granted daily.

Ivonne

October 26, 2013 at 3:00 amThanks Flora, I am sure that this beautiful article will move many hearts, we were happy to have you¡

Flora

October 29, 2013 at 6:18 pmThank you so much Ivonne! I loved my time at the clinic 🙂

casino-svea.se

December 7, 2013 at 11:39 pmDet finns flera fördelar som är värt att överväga, om du får

den mest online casino 2013 från tabellen.

zeenwaul

June 30, 2015 at 5:53 amGreat work! Keep on.

Coping with La Paz: a City of Cold, Colour and Contradiction

July 30, 2015 at 6:02 pm[…] to a recommended Spanish school, was unfortunately also a forty minute walk from my work at the artificial limb clinic – so while I enjoyed wandering through the streets each morning, my lungs were less than […]