This is the house I was born in.

It’s the only family home I’ve ever known.

This is where my parents brought me as a baby in March 1988; to a house they’d decided to put a mortgage on when they realised they were about to become a family. They’d only been together for six weeks when she discovered she was pregnant.

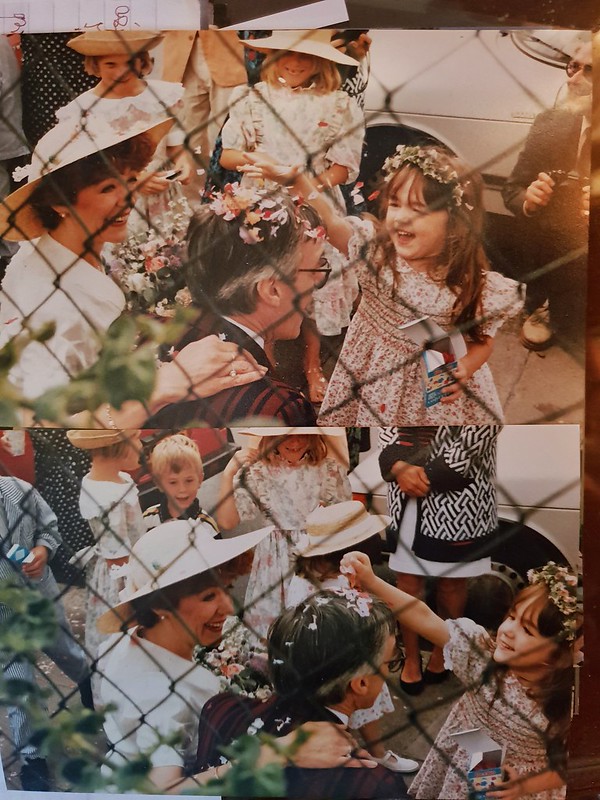

My parents first met ten years earlier. He’d directed her in a play in 1977 (she was his leading lady), but he was already due to be engaged and so nothing could happen between them.

Ten years later and after his divorce, he left a message on her answerphone asking her to lunch.

The rest is history. Thirty years of it, in fact. And it’s a history I’m now responsible for preserving. Now, this house and its contents are all I have to remember my parents.

Losing your parents turns your world upside down

2018 has been the most difficult year of my life. Since my dad’s death last October it feels like I’ve spent more days crying in these six rooms than living in the outside world, and it’s been utterly exhausting.

One of the hardest things about grief is that there’s no rule book. It’s completely up to you – your body, your mind, your emotions and your intuition – to parse how to act, think, and feel your way through the grief-cloud. Your friends are supremely cautious about giving the wrong advice or adding any further stress, so they’re gentle with everything they say to you. Much of the time I hear, “We can do whatever [it is] you want.”

But that’s the problem. I have no bloody clue what I want. And what may feel like appropriate behaviour (i.e. spending your days sobbing on the carpet) is fundamentally flawed, because you’ve been through such huge trauma that your instincts are all over the place.

Take this house, for example. I moved back here just over a year ago in July 2017 when my dad was dying so I could help care for him. The timing was bizarrely appropriate: my flatmate Emi was heading to Nepal and India for six months so I wasn’t sure what my housing situation would’ve looked like anyway.

Except once my dad died last October, I didn’t leave the house. I couldn’t.

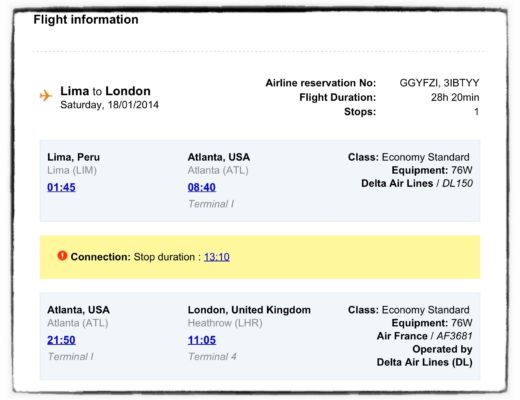

Instead I lived in a blur. My world became a confusion: predominantly crying in London, alongside occasionally telling myself I could still travel; that being abroad could still make me feel normal. In the first half of 2018 I headed to Cuba, Spain, Antigua, and Holland – but I still didn’t question my home base.

So I’ve somehow spent almost ten months living in the house I grew up in. By myself.

There are reasons for this, of course. For a long time I couldn’t even contemplate the idea of living elsewhere because this house is where all my familial memories are – and because being here allows me to remember them, and cry about them, and mourn them.

But I’ve been so careful to allow myself this private grieving space that I’ve overlooked something much more important: is being alone here actually helping me?

Losing your parents means you compare yourself to them

For a long time I’ve classed myself as an extroverted introvert. I love being around people and I thrive in social environments, but when I need to recharge it’s all about being by myself. Now that my parents are no longer around, it’s acutely easy to see my behaviours aligning with theirs – and to judge myself accordingly.

My mum was a born socialiser. Whenever I came home from school she’d be sitting with her friends around our kitchen table gossiping with cups of tea, and we’d always joke that Mum could make instant friends with anyone, even in the queue at the post office. In comparison, my privacy-preferring dad was more likely to choose a night at home than any number of social invitations my mum tried to entice him into.

After Mum died, I noticed that our family house grew immediately quiet. While I quickly went back to university and then moved to San Francisco for my year abroad, Dad barricaded himself here – one man with his impenetrable fortress of solitude – and that’s how I began to view this place too. As a quiet, empty set of rooms, with way too much space to think.

I’ve spent most of the last few years terrified that I’ll end up alone like my dad – even though the crucial difference is that he was clearly happy being by himself. Yet conversely, I still need time and space alone to grieve and cry (the age-old adage of being stuck between a rock and a hard place has never felt more appropriate).

It’s made sense for this house to be my place of solitude this past year. This house means more to me now than it ever has. It’s been the one constant throughout my life: first a place of ultimate familiarity and comfort, then a place to grieve with my dad about the loss of my mum, then a place to calmly remember her, then a place to watch my dad’s declining health, then a place to grieve for him alone.

I have boxed myself in here. Self-imposed isolation. Surrounded by photos and objects and furniture and so many goddamn memories at every turn, which all act simultaneously as beautiful and heartbreaking reminders of who I’ve lost.

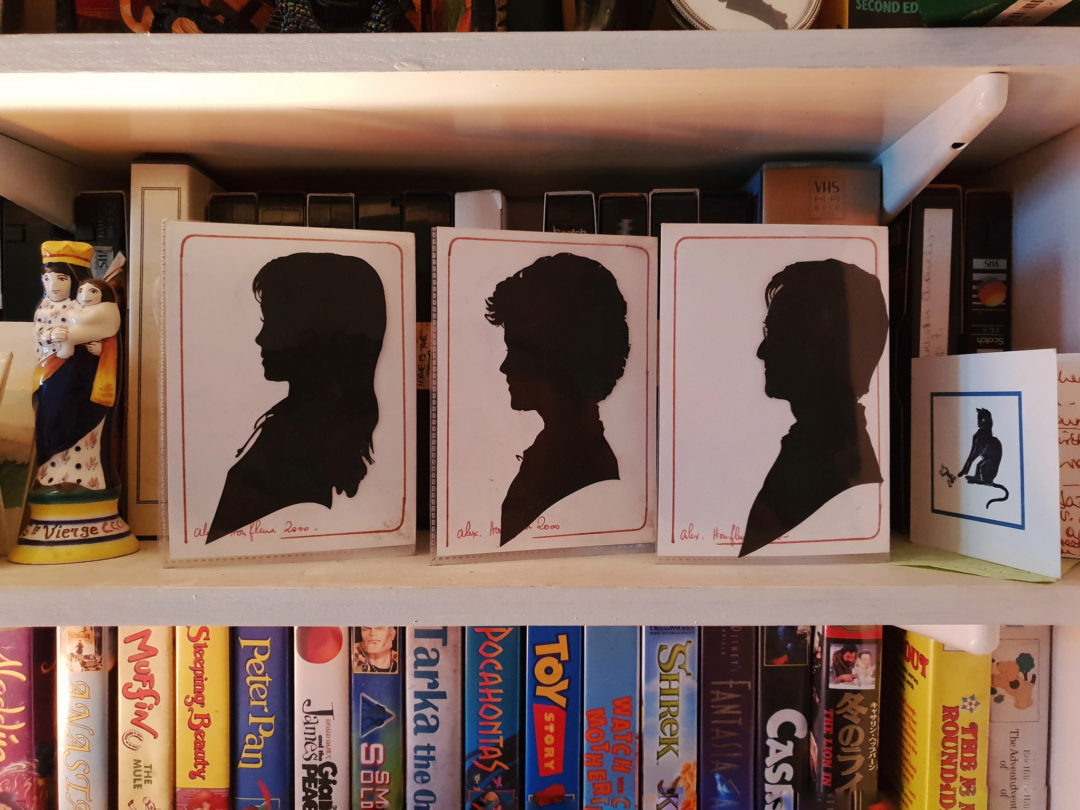

These are the details of my house: the inexplicable details which now mean everything to me, but mean absolutely nothing to anybody else.

There are the orange and blue shadows which fall onto the bathroom floor every afternoon when the sun is shining.

The chipped paint on the bannisters in the hall where we used to leave Post-It notes for each other, explaining what we were up to that evening. Her choir practices, my music lessons, his theatre rehearsals.

The elastic band I placed on the one squeaking stair so I’d know to avoid it and not wake him up when he was dying.

The marionettes she brought back from a visit to Indonesia, which my dad hung on the back of the living room door and posed them holding each other’s hands.

The wild blackberries which have always grown in the garden bushes, and which he made into crumble in the autumn – along with shop-bought apples and a secret ingredient of canned mango to make it smooth and creamy.

The green glass bottles she placed at the very top of a door in the kitchen we’ve never opened.

The hole in the middle of the lawn where he planted an apple tree in memory of her.

The theatre masks he collected from Greece and Japan and hung up in his study, which used to haunt me whenever I ran past the open door to the bathroom in the middle of the night as a kid.

I’ve tried my best to make this place my own. Slowly, carefully, I’ve begun to place my own possessions around the house and make it a mixture of our shared past and my sole future.

But I’m still living amongst their memories. Because what do you do with the sum total of two people’s lives who no longer exist? She was sixty two when she died. He was seventy nine. That’s a hundred and forty one years worth of life! All of which I’m responsible for; all the parts of their lives that they chose to keep.

And I still don’t really know what I’m doing. Or if I even want to do this.

I don’t know how to clean two floors of a house adequately, so the dust collects above doors and on carpeted stairs and underneath heavy oak furniture which once belonged to my grandmother.

I look around at bookshelves heaving with texts I’ve never read and probably never will – but they’re a lifetime of two peoples’ theatrical study and theatre work, and my heart breaks at the thought of giving them away.

I have a hundred questions I can never know the answers to: where did they find the cherub which hangs above the stairs? Why didn’t he tell me how to unlock the second set of garden doors? How do I fix the strange leaking patches in the ceiling? Do I really have to find a chimney sweep to clean the fireplace?!

And sometimes I just can’t bear to move objects from their years-old positions when I know my mum was the last person to decide where they’d be placed. She was the last person to have ownership over them, and I can’t bear to eradicate that.

You can’t heal in the same environment where you got sick

In January I wrote an article about my search for ‘home’. I said that, after years of travelling with an internal need to keep moving, I now wanted to stay very still in a place of comfort and wait for this grief to wash over me. It’s taken a while for me to realise that waiting for grief to do its thing doesn’t actually work.

Wherever I am, I’m still going to feel this grief. Yet I’m making it infinitely more difficult for myself: no longer living with housemates and also being in a long-distance relationship means I’m primarily facing the day-to-day hell of that grief alone. And it’s too much.

I’ve seen a quote crop up a lot recently: you can’t heal in the same environment where you got sick. As so often happens, this has been like a lightning bolt of realisation. Maybe the house where I grieved the sudden loss of my mum and spent months watching my dad die isn’t where I should be now?

I’ve always seen it as a safe space, but in actual fact my house now feels somewhat toxic.

I’m also giving it too much power. This is JUST a house. It is just a building. It is not the physical embodiment of my parents. Not being here doesn’t mean I’m disrespecting them or their memory. Not living here doesn’t mean I’ve failed.

And another thing to bear in mind? Home isn’t always in just one place.

The place you call ‘home’ is your choice

The turning point of this thought process happened a few weeks ago. At a recent summer’s evening on a London rooftop, surrounded by many of my blogger friends, we were celebrating the wedding of two of our own, the stunning couple that is Paul and Karen from Global Help Swap.

As I chatted about the concept of ‘home’ to people who’ve known me for almost a decade, both online and off, I realised that the Flora they know is fundamentally a traveller. An explorer. Someone who breathes excitement, loves impermanence and adores challenging herself with a myriad of adventures around the globe.

Alongside many of these blogger friends I’ve travelled to Spain, Antigua, Scotland, the Philippines, Holland, and South Africa. We’re a group who think nothing of criss-crossing the world to spontaneously meet each other for beers – and that style of travel, that impromptu way of life, is a huge part of me. I’ve just lost sight of it for the last few years.

Losing your parents is traumatic – which means that right now, I’m going to be scared of whatever changes happen. I’ve forgotten what it’s like to have the courage to start over in a new place. But I’ve done it dozens of times before, in Florence and Norwich and San Francisco and Ecuador, and I know just how incredible it can be.

Although the idea of leaving my house fills me with fear, it doesn’t necessarily need to be a big deal to move somewhere new. This house will always be here, as long as I want it to be, and the memories won’t disappear just because I don’t live amongst a cascade of them every day.

That night after the wedding celebrations, I came back to my family house alone. I walked in through my familiar front door, climbed the stairs, and crawled into a huge bed by myself. Comfortable, certainly, but not enough anymore.

I’ve reclaimed enough of this house for now. Perhaps it’s time to move onto someplace different.

Have you moved on from the place you called ‘home’ after a trauma? What do you think makes a house a home?

NB: All the images in this post were taken with the new Samsung S9, which I’ve been trialling out thanks to Three.

11 Comments

Fiona

August 26, 2018 at 7:20 pmI wish you well on your journey of life Flora and I love reading your travel blogs. Advice, if I was to give it, would be sell the family home, take the memories but make your own in a place that excites you. Maybe travel to my home town Melbourne.

Flora

November 27, 2018 at 7:23 pmThanks so much Fiona 🙂 I really appreciate your advice, although I don’t think I’ll be selling the house just yet – perhaps it’ll feel right when I actively know where else I’d like to live!

frederick

August 27, 2018 at 8:20 amDear Flora Hello thank you for your blog and the words and the photos it is very hard to cope when loved ones die after My Mum died I had to move My Dad had died some years before the home was rented so I had to leave my Birth Home the Council said I had to go .That shook me as I knew no other place after a time I was allowed to move to where I live now it is in the same Village where I have lived all my life I am blessed with lots of friends however I feel that as I still have things of Dad and Mum I have one foot in the present and one foot in the past.I think back over the years as to what they did with there lives and my life is not a patch on them .It is very hard at times .However I carry on please remember Flora you are on my prayer list .good wishes for your future. Warmest Regards Frederick

Flora

November 27, 2018 at 7:25 pmIt’s always so lovely to read your comments, Frederick 🙂 I’m so sorry you had to leave your birth home after losing your parents – that must have been difficult. But it’s truly wonderful to hear you’ve got good friends around you!

Mike Sowden (@Mikeachim)

August 27, 2018 at 1:32 pmAhh. This is so hard. And you sound like you’re on the verge of flying apart with the stress and pain of it.

In my case, my mum’s house is uninhabitable, so it’s all shut down and I’m elsewhere while I empty it, ready to sell. Being elsewhere makes it feel more like a transition, not an ending.

I’m glad you’re thinking of travelling. Because – go be someone else for a while. When we travel, we have the opportunity to edit ourselves into something a little better, stronger, more optimistic, and act like it until we feel like it. So, why not?

Sometime soon, I’m moving to York for a bit. Why not grab a flat in York and do the same? Or Harrogate, where Beverley is based right now. Or somewhere else you quite like, with people nearby to have coffee with. Go elsewhere. Be another Flora for a while, with enough stability to enjoy the thrill of elsewhereness, but enough routine and homebasedness to not feel untethered. Maybe it’d help.

Sharon H Miro

August 27, 2018 at 3:51 pmThis broke me…I was 62 when my parents died, and I can testify that those feelings you express here crop up at any age.

It is hard becoming an orphan. You no longer have that completely unconditional safe harbor to come home to. In many cases you have to be the safe harbor for others. And there is that sense of rootlessness that can be overwhelming.

In time I saw it as another gift from them: affording me the freedom to be, wherever and when ever I wanted. I wish you steady in your explorations of the next stages of your life.

IslandMomma

August 27, 2018 at 6:12 pmWhat Sharon says is so true, my dad died at the end of 2015. He was 93 and I was almost 69, but his death released all sorts of emotions, some of which I thought were long-buried. We all have our different ways of dealing with loss, and sometimes a loss is harder or easier than we thought it might be. But this is not the sum total of who you are, and you clearly know that essentially. If I have any advice, it would be to give yourself some more time to re-acquaint yourself with yourself, perhaps a slightly different person from the one you were. I’ve observed people act in haste, and I’ve observed people dwell on things for too long, and neither is healthy. Travel is always helps to put things into perspective (IMHO). Whatever, I wish you much luck and happiness, whatever lies ahead.

majw13

September 6, 2018 at 9:21 pmPeople say that home isn’t a place but a group of people, but when someone suddenly dies, then home does somewhat become a place because it’s the place where you had the most memories with them: the place where they touched everything, fixed everything, the place they tidied, maintained, breathed, farted, burped, lived. And you want to remain there as a way to remember them because what if the next person tears out the stairs he built? Or tears out the kitchen sink you built together? The things that belonged to them, the things they did become so much more important in perspective after their death because we all know this to be true: nothing stays forever here. In 70 years time, no one will remember them.

Unless we pass the stories on. There’s a quote that I keep remembering after my dad suddenly passed away: “Some people look for a beautiful place. Others make a place beautiful.” And if you think about it, what your parents called home was not that house. Sure, you grew up in it and that was the place you knew since birth, but to your parents, it was another page in their book. Their home was you, with you. And I don’t know if you believe in a heaven or hell, but surely, their home is still with you. They’ve channeled the things they learned, their love, their wisdom, their faults, and their hopes into you. It doesn’t mean that you’ve become a copy of them, but it does mean that you carry them with you. And what you carry with you can be shared with other people.

My dad loved to help people. He’d collect wood, metal, random things that seemed like trash, and then bring them all out if someone needed this fixed or needed some extra packing material or something. He had a contagious smile. He put his whole heart into raising this family. These are “things” I can share with those around me. His values, his heart, his life – and in making a place a beautiful, you’ll slowly start to see that home really is a group of people. You’ve made homes in everyone’s hearts just like your mom and dad did in yours.

Home Is What's Left Of You • Fevered Mutterings

September 21, 2018 at 7:20 pm[…] has been dealing with the death of her father, and writing heartbreakingly well about it. Read her letter to her family home, and her post about losing both her parents before her 30th […]

Anna

November 21, 2018 at 11:50 amThank you for your blog. For me it’s also the noises in the house. My parents died in a car accident 8 weeks ago. Both my brother and I have found ourselves just sitting in the living room listening to the old clock on the wall, the familiar clunk of a particular floorboard as someone walks along the corridor, the bathroom door handle sounds different to all the rest. I can’t take the floorboard or the door handle, but I can take the clock and it will continue to be the backing track to my existence in the years to come.

Flora

November 27, 2018 at 2:19 pmOh Anna, I’m so sorry to hear about your parents. I know just what you mean about the noises – even though it’s been a year since Dad died I still catch myself interpreting the creak of a stair or the air whistling through the keyhole as an action of his. Muscle memory (or whatever we call sound-to-meaning memory) is very hard to reset.

Luckily I do now find comfort in some of those noises 🙂 They’re bittersweet but the emphasis is now more on the sweet! It’s lovely to think that something of them is still left in this house via those familiarities.

If you ever want to talk, please feel like you can message or email me – I’m here whenever 🙂 Sending lots of love to you xxxx