Hugo and Consuela have a framed photo of Che Guevara above their fish tank.

This middle-aged couple, my casa hosts in Santa Clara, have just bought three slices of peso pizza from the hole-in-the-wall round the corner. We sit at their small kitchen table, fans whirring overhead: I nibble at a corner of the greasy slice while Hugo sips on his mug of red wine, poured straight from the freezer, then asks me, “How is Tony Blair, in England?”

My Spanish is proficient enough to explain my opinions on English politics a bit – although I don’t bother pointing out that England’s current prime minister in the summer of 2014 is David Cameron, not Blair. Instead, I say it’s sad because some of the UK’s popular political parties don’t think we should welcome people from other countries or look after those who are poor and vulnerable.

Then, knowing I won’t get many chances to ask, I mention Raul Castro and the current Cuban regime. “Is it good here, the Communist government?”

“There is a line, in Cuba,” Hugo says, thoughtfully. “It’s not totally straight. Some people have a bit more money than others, but there isn’t much of a difference. People aren’t millionaires.” He thinks for a moment, then says decisively, “There aren’t many problems here.”

Getting up to clear the table, Hugo drinks the last of his wine as he walks. “Me gusta nuestra gobierno!” he mutters. I hear occasional words: ‘La revolución…’ ‘Fidel, el Che, Raul…’

“Si, el Che…” I venture. Is it still OK to ask him questions? I point at the frame on the wall as my host turns back to look at me. “This picture is from when he was young?”

“Mi hijo… Mi jeffe,” he says, nodding. My son, my leader. Hugo puts both hands to his chest and glances at the bearded face with a beaming smile.

“He was an incredible person, an incredible character. There is no other person like him.”

Getting to grips with communism in Cuba

One of my major reasons for visiting Cuba in 2014 was to try and understand the political regime which Cubans had lived under for more than fifty years. Despite being a tourist, the way I appeared that summer was the most ‘non-English’ I ever have: being semi-fluent in Spanish with a pretty decent tan allowed me to successfully pass for a native Colombian with a number of Cubans.

I thought my luck was in.

Yet despite my best efforts during a month of journeying around the island, learning about Fidel Castro, his brother Raul, their communist regime and what Cuban people felt about it all remained frustratingly elusive.

“There is no feat in which the people of Villa Clara have not been massively present” — praise from a building-sized Castro in Santa Clara

On the surface, the influence of Cuba’s 1959 revolution is obvious enough.

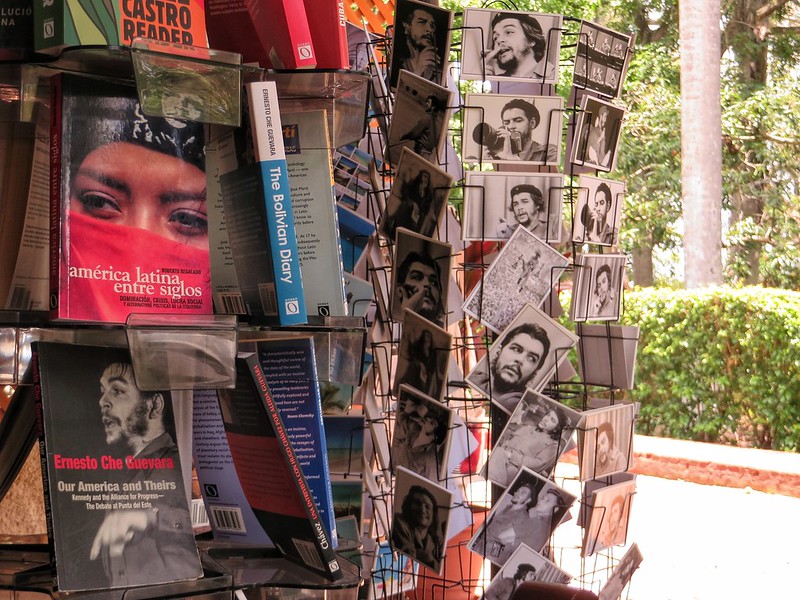

This is a country where every wall is decorated with revolutionary slogans and artwork; where lampposts are marked by crucial revolution dates; and where Che Guevara’s face is replicated in every place possible.

Yet some of these anonymous messages mean more than others – like the signs which indicate a ‘CDR’ zone.

Observing the legacies of the revolution

Shorthand for ‘Committees for the Defence of the Revolution’, the CDR was set up by Fidel Castro in 1960. Although it officially acts as the ‘eyes and ears of the revolution,’ promoting social welfare, the CDR is also viewed by many as a means of mass surveillance: permanent files are kept on each citizen and all their activities are recorded.

The knowledge that each neighbourhood had members keeping tabs on their communities was unsettling, and it eventually influenced the way I looked at the country. With each Cuban flag I saw – from those tucked between the vegetables of a farmer’s stall, to others decorating a children’s playground – I couldn’t help doubting the legitimacy of why they’d been placed there.

Were the people in Cuba genuinely patriotic, or were they being forced to put these flags up?

Time to talk to some Cubans…

It’s easy to search for the supposed signs of a regime and draw your own conclusions, and even easier to end up with the wrong answer. To get any real idea of how Communist Cuba worked, I needed to ask people what their lives were like.

I realised pretty quickly that nobody wanted to tell me.

In the summer of 2014, every Cuban I met had been living under Castro’s rule for fifty years: long enough for anyone who’d experienced a pre-revolutionary Cuba to barely remember it. As the children and grandchildren of revolution, most knew nothing of ‘old Cuba’ except through stories from their aged relatives.

It didn’t help that I had no idea where to start. Somehow I’d assumed that simply mentioning ‘communism’ would be enough to instigate a conversation, but apparently not. When I spotted a house acting as a pseudo-museum for the Cuban Five (a group of men imprisoned in the United States for two decades on spying charges) the woman who ran the museum was completely uninterested in talking to me.

Either she didn’t want to talk about what they were doing, or she couldn’t.

Eventually I realised that to grasp anything of importance, I had to be satisfied with simple observation.

A different way of learning

In Sancti Spiritus, I sat and watched telenovelas with my host’s Cuban grandma, and together we saw repeats of the nationalist broadcasts which aired after every episode: a segment called ‘Este Dia’ showing three events from that date through history, accompanied by speedy biographies of revolutionary figures and crackly outdated graphics.

In Cienfuegos, I played dominos with two old men in their back garden while a plane flew overhead. “De Miami,” one of them said, identifying the flight path even as he slapped down his plastic domino with relish. They told me the journey took just 45 minutes, but neither of them had ever left the island.

In Trinidad, I listened to high school children singing the national anthem at 8am from my casa next door, as my hostess Odalis mouthed the words quietly to me.

She knew the anthem was revolutionary, dating from sometime in the 1960s, but she couldn’t remember if there was another national anthem before this one.

And when I reached Santa Clara, it was time to investigate everything ‘Che’.

Santa Clara, a city-wide Guevara memorial

The central plaza of Santa Clara is home to the Che Guevara Mausoleum, a memorial which holds the remains of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara. He’s interred alongside twenty-nine of his fellow combatants, all of whom were killed in 1967 during an uprising in Bolivia.

In the shadow of a giant plinth inscribed with a farewell letter written by Che to Fidel, two boys named David and Santiago played shooting games on the marble steps. ‘Eres muerto!’ one shouted to the other, prompting both boys to collapse on the ground with arms flung out while their exhausted mother looked on.

In Santa Clara, I started to properly understand just how iconic Che really is for the people of Cuba.

Inside a museum celebrating his early life, I walked past family photos, a doctor’s coat he wore, his mugshot when he was arrested as a teenager in Mexico, the chess set he played with in the Sierra Maestra, his dentist equipment, his syringes, and his binoculars. There was even a peach stone carved with his likeness, resting inside a glass cabinet.

It almost bordered on worship.

Then again, that worship seems pretty appropriate. An Argentinian doctor-turned-revolutionary, Che Guevara pledged such allegiance to Cuba that he died fighting to maintain their revolutionary spirit, and it made him a national hero.

The man is a symbol both of the Cuban Revolution and of radical revolution around the world – and the added fact that he was seriously attractive only seems to help.

The commercialisation of Communist Cuba

I do wonder what Che would have thought of all the adulation, though. Fifty years after death, his face is essentially a capitalist vehicle: his iconic photo is plastered onto t-shirts, fridge magnets, tie-died bags and cooking aprons, yet many people have no idea who Che Guevara is.

Something I doubt he’d be happy about.

So how do Cubans react to this commercialisation? Well, in Cuba at least, most seem more than happy to sell his image, his reputation, and his name.

That’s why it’s difficult to ascertain where the monetary gain found in Che ends, and the real patriotism for a radical, anti-capitalist figurehead begins.

But maybe people across the world are so enamoured with Che Guevara because of what he represents as a person. He was confident, passionate, unafraid and therefore absolutely inspirational – even if they don’t know the ins and outs of the communism he championed.

And as a martyr whose reputation now remains ultimately unchangeable, this very attractive man still holds a great deal of power.

The Cubans who still believe in revolution

Back in Santa Clara, Hugo and Consuela are calling me ‘the writer’, because I spend my afternoons scribbling in a notebook.

“Do you have a diary?” Consuela asks, as they rock back and forth on their matching chairs. “Che had a diary, didn’t he?” Consuela’s words sound more like a statement than a question.

“Si – the most important diary,” her husband agrees.

Suddenly, Hugo asks if I want to take a photo of him. When I nod, he opens a cupboard door to bring out a red board pinned with medals: some from the Bay of Pigs, others from revolutionary battles, and commemorative ones which celebrate ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty years since the revolution. Right in the centre is a badge, made of cloth and faded from wear. ‘Liberte o muerte,’ it reads. Freedom or death.

I realise why Hugo called Che his jeffe the day before. This man in a rocking chair fought as a guerrilla during the revolution, and the infamous Guevara really was his leader.

Two years ago, I found it too difficult to explain how I felt about Cuba and its politics, and was worried I’d be making assumptions about a country I know nothing about. Granted, I’m still woefully uneducated about whether Cuba is more aligned to a communist or a socialist system, and I doubt I’ll ever properly understand it.

Yet the recent news of Fidel Castro’s death heralds the possibility of a new era in Cuba, and it’s painfully obvious that Cubans are equally concerned about what that might look like. Days after Castro’s death, I watched a news story with a split screen: on one side, Miami’s Cuban neighbourhoods were filled with celebratory parties, while on the other, Havana’s streets were quiet and empty. Other footage showed sombre citizens standing in Santa Clara plaza near their beloved Che, every face tearstained and shocked.

It’s hard to say which reaction is more representative of the Cuban peoples’ real feelings, but I couldn’t help thinking of the the repressive system which is Castro’s ultimate legacy. Though his healthcare and education policies were fantastic, he still ruled almost every element of Cuban life, didn’t allow anyone to leave the island without permission, and was the cause for thousands of people escaping to the seas on boats and rafts in the hope of making their way to the US coast.

Cuba’s uncertain future

Many countries celebrate the life of a lost leader, even as they mourn his death – and because Che Guevara died before his time, making him into a martyr was easy. Yet it remains to be seen how Fidel will be remembered, particularly when many people maintain that everyday life in Cuba has been extremely hard for decades.

One of the final revolutionary slogans I saw in Havana read, ‘faithful to our history.’ Alongside, the faces of Julio Antonio Mella, Camilo Cienfuegos and Che Guevara were topped with three words: ‘Study, Work, Rifle’. It’s the motto of Cuba’s Young Communist League, and gave me chills even as I read it.

Who are they expecting to be faithful? And at what cost?

9 Comments

Ryan

December 16, 2016 at 5:48 pmThis is such a fantastic article Flora. Love how your experience there is also such a pin point look at Cuban life even though it partially remained elusive. And the fact that the house you stayed in was involved in the revolution, that’s incredible. I hope to get to Cuba sometime soon…to see the culture and hopefully dive deeper than the surface like you did. I honestly didn’t know much about Che and Fidel besides what I’ve been fed to believe in high school, but I want to know much more after your story.

LC

December 21, 2016 at 1:46 pmI travelled to Cuba earlier this year (your articles were so helpful in advance preparation and for this I thank you). Everything you’ve written about here, resonates with me and what I felt when I was in the country. There’s a lot going on beneath the surface, but in not speaking Spanish, I couldn’t scratch it as effectively as you have. Strange place. Intriguing place. All I know is I feel for the Cubans, and I hope for better days for them.

pen2paint

December 21, 2016 at 2:22 pmI went to Cuba in Feb of 2016. People were more wiling to talk than I´d heard but I speak some Spanish like you Flora. Most are hoping that when the Castros both die off, communism will go with them. There are leaders in Miami waiting, so they say. One GREAT book I read about the history of Cuba which I highly recommend is Bacardi and the Long Fight for Cuba. I wish I´d read it prior to going. I also wrote a little book of short stories and travel tips about my adventures-you might like it, on Amazon called Cuba for Mama, A Daughter´s Journey 2016. I enjoyed reading your article, Flora. Keep them coming! You always have a bed in San Diego if you´re so inclined to travel, I love travelers!

Alan

December 22, 2016 at 1:42 pmGreat article, Flora. I was in Cuba in 2012 as part of a group of lawyers who went to study the differences in the American vs. the Cuban legal system. I’m more than twice your age and was 12 when Fidel ousted Batista. I knew many Cuban refugees and remember the Bay of Pigs, remembered Che’s exploits and death, etc.

I met many law students at the University of Havana and at the Jose Martinez Institute, and most of them were very comfortable talking politics with us. It was part of their program. Unlike American students, who challenge authority and society almost without exception, these students wanted to explain why their system was just and correct. As a former student of the 60s, it was clear that while these students felt free to chat, none of them argued with the party line. Perhaps it was a requirement for admission to school in the first place. I am confident they believed what they were saying.

Outside of the academic environment, ordinary Cubans were largely afraid to say anything other than to sell you coffee or to answer some factual question to help me improve my Spanish. The exceptions were the jinoteras hanging out all over Havana and at hotels elsewhere. They will discuss politics but as an explanation for how they became hustlers or hookers. Even then, however, they speak of politics generically, that is, to explain their own circumstances. They look at themselves as anomalies, not as dissidents.

As you say, after having one school of acceptable thought for 55 years, few people in Cuba even know about alternate forms of policies. You can see this in odd ways. Some of the very bright law students loved Law and Order which they get on TV. Many believed that American criminal trials last about an hour, as depicted on that show, they were stunned to hear that some of our trials last weeks or months, and could not grasp that the defense may spend hours grilling the police. A very revealing event occurred when Cuban television broadcasted the second US Presidential debate in 2012 between Obama and Romney. It was a town meeting format with the candidates walking about the stage. We were in an inexpensive hotel with just one television so about 10 of us sat together in a common area. Some hotel staff was assigned to stay with us in case we wanted to order drinks from the bar.

Neither of the staff people spoke English so they didn’t really know what was going on. I asked one fellow what he thought was going on. He thought the President was being interviewed and that Romney was acting as a commentator. When I explained what the debate was, he clearly was skeptical. Then, however, Romney walked over the the questioner in the audience and passed within a couple of feet of President Obama. One staff person looked stunned and asked me why they let someone walk so close to our President. I explained that during the debate, either candidate could stand or walk wherever they wanted, and that either could say whatever they wanted. The staff guy said to me that this was a bad way for a leader to be treated, and that in Cuba people would never argue with their leaders like that. He very definitely disapproved.

It will be very difficult for people who believe this way to accept that criticism of the government is not disloyal and unpatriotic. I was in Iron Curtain countries in the 60s, but there no one believed in the government although it was very repressive. The ordinary citizen in Czechoslovakia or East Germany expressed their hatred of the system in many ordinary but daily ways. I saw none of that in Cuba, and to me it was even more scary in a way.

I am not so sure than many ordinary Cubans even think of an alternative political sysem. We shall see, but the traveler to Cuba probably won’t be able to have what most Americans would call a discussion about politics. There just isn’t anyone who will take the side or the argument that favors change. Not yet, anyways.

Ria

November 30, 2017 at 11:21 pmIn 2010 there were national debates on how the country should be governed, how the economic problems (due to years of imperialism, debts, the US blockade and natural disasters) could be overcome without completely succumbing to market mechanisms. 9 million people (in a country with a population of 11.4 million) participated in the debates, where critiques were welcomed and encouraged. 68% of the original policies were modified according to popular opinion. Anybody propergating the myth that Cuba is a dictatorship in which citizens have little to no say in what happens have obviously not studied the political economy, or the running of the country in any detail beyond the mainstream press dedicated to demonising any country opposed to imperialism.

The students were probably justifying their system because they understand how it benefits them- it is more than free education and healthcare, it is the complete dedicated of the state to its citizens. During the special period of economic crisis in the 1990s, there was a catastrophic drop in GDP, but unemployment rates hardly changed: the government ensured the Cuban people were being given a minimum wage and did not starve.

As a law student / graduate from the US, I don’t see why you expect Cubans to have a thorough understanding of the American judicial system (most of my friends wouldn’t have a clue how they work or how long they can go on for) when you obviously do not have any in depth knowledge of the Cuban political system. Your remarks on that also imply that police in the US are held accountable for their actions, which is laughable and I would encourage you to visit Black Lives Matter if you would like to learn more about the multitude of murders the US state police have committed and remained without punishment. When 78% of people in America don’t even see trial (and the entire judicial system is based on racial prejudice) I don’t think it’s your place to assume any patriotic or moral superiority on Cuba and Cubans.

The Travel Tester Favourite Blogs December 2016

March 23, 2017 at 10:56 pm[…] Che, Castro and the Legacy of Cuba’s Communism – Flora The Explorer […]

The Travel Tester Favourite Blogs January 2017

May 2, 2017 at 12:52 pm[…] Che, Castro and the Legacy of Cuba’s Communism – Flora The Explorer […]

Ken Barnes

August 16, 2018 at 2:18 pmWow, I guess some of thoet poor, ignorant Cubans are really dumb, and gullible, if they believed you were Colombian because of some accented Spanish and a tan. No superior, sophisticated European n Spain would ever believe such a thing. Jus dumb Cubans, right? 🙁

Bill Streifer

October 19, 2024 at 6:52 pmI’m writing the biography of Lionel Martin, an American reporter who resided in a suburb of Havana, Cuba from 1961 until his death in 2019. He loved chatting with everyone (in both English and Spanish), so if you had any interaction with him, I’d like to discuss that with you.