The Galápagos Islands are infamous for their scenery and wildlife. They’re a dream destination for thousands of people around the world who crave the crystal clear waters, the multitudes of colourful fish, the diving and snorkelling opportunities, the bizarre plethora of confident sealions and skittering iguanas, and the chance to sit back and relax on a cruise boat to experience it all from.

Since the days of Darwin, the islands and their unique ecosystems have fascinated so many people that they’re now regarded as Ecuador’s crown jewel: islands that rightly receive a vast majority of all South American tourism.

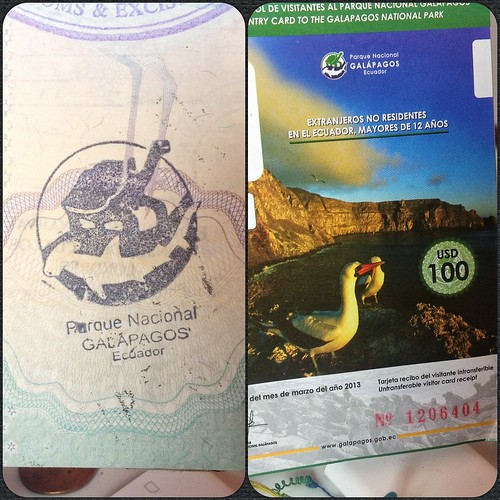

The Galapagos National Park organisation duly capitalises on the place, charging a $100 entrance fee to every foreigner who sets foot on the island and ensures the archipelago is protected as much as possible from the effects of 160,000 tourists each year.

But there’s a much darker side to the Galapagos than a lot of people realise. The tourism industry is ever growing and adapting to the needs of its visitors; and as it grows, it seems like the islands are being destroyed as a direct result.

How does tourism affect the Galapagos?

There’s no doubt that tourism changes whatever it touches. It’s reported all over the world: thousands of hiking boots wearing through the rocks of Machu Picchu; tourists’ suncream leaving oil trails beside coral reefs; even my own mother being guilty of ‘borrowing’ a few pebbles from the red sands of Petra.

Because where something beautiful, fascinating and relatively unique exists, so do tourists.

Nowhere is this tourist presence more dangerous than in the Galapagos, where each species depends on its own delicate balance of nature in order to survive.

Luckily, among the groups of tourists that throng the beaches, mangroves and rocky walkways of the Galapagos, most are breathlessly aware of how delicate the environment they’re exploring is. Tour guides are consistently vocal about how to behave. You should never get closer than a metre to any animal; never offer food or water; never try to hold or touch anything.

But that doesn’t seem to stop a lot of people from breaking the rules. On my cruise, a Canadian woman poured a capful of bottled water into a rock fissure, so a tiny bird waiting patiently beside her could dip his beak in and drink. Our guide was highly disapproving.

“You cannot do this,” she said, as the entire group started snapping eager photos of the bird. “The birds know people have water, and they wait for it. Your lips have touched the bottle top – this bird may get an infection now.”

It’s as simple as that: literally any interaction made with a Galapagos creature has the ability to destroy a part of their lifestyle, and could lead to catastrophic consequences.

A short history of animal lifestyles on the Galapagos

There really aren’t many places in the world where humans and wild animals can be at such close quarters with each other. The Galapagos creatures have such little fear of people because the lack of land predators have caused these species to evolve without the flight instinct so common in the rest of the animal world.

Five hundred miles from the South American coast, the animals living here had little to no contact with humans until the 1600s. But for at least four centuries, the islands were consistently exploited by humans who felt certain that a productive lifestyle could be forged there.

First came pirates to bury their treasures and hide from potential captors, then whalers who killed giant turtles to extract their fat, and seal fur hunters who almost wiped out the sealion population.

When Charles Darwin arrived in the Galapagos in 1835, he was fascinated at the ability of these animals to adapt and thrive in such a harsh environment: one which he himself couldn’t wait to leave after just a few weeks of research. His ship, like many others at that time, was loaded with a number of giant turtles, to be used as a source of fresh meat for the shipmates on the long journey home.

In later years, short lived prison colonies and workcamps were established on some smaller, outlying islands, and eventually small groups of colonisers – families, occasional scientists and researchers – would start new lives on the islands, beginning to farm the land and grow crops in the harshest of environments.

Through all that time, various animals brought to the islands via those humans – whether purposeful or accidental – have created huge threats to the Galapagos environment. Wild goats, feral cats, dogs, pigs, rats and parasites are just some of the introduced predators that affect the numerous native species; eating their food, attacking their habitats, and leaving them defenceless.

And yet the animals that live on the islands are still here – after thousands of years of adverse conditions, and a few hundred of intense human meddling. Each species only survives because they’ve adapted their lifestyles to combat the harsh sun, the lack of vegetation and a rocky landscape inhospitable to most.

But it’s getting even harder now for these animals to survive. And not just because of the tourist influence.

The impact of climate change and pollution on the Galapagos

The biggest threats to the Galapagos are more prevalent now than at any other time in history. Climate change is wreaking havoc on the islands in a number of ways.

As the water temperatures rise and rainfall increases, the sea currents change: currents that many animals in the Galapagos food chain depend on for sources of food.

Sealions and fish are swimming out farther and farther in an attempt to find fresher water; breeding patterns of iguanas and tortoises are changing; and animals are being forced to eat foods that aren’t as suitable for their diet, simply because they can’t find the right things.

The combination of climate change and a lack of human respect for the delicate ecosystem of the Galapagos is also proving disastrous.

There are growing problems with illegal fishing, overfishing, an increased generation of waste and, despite the best efforts of the national park authorities, improper waste management.

A Sally Lightfoot crab scuttling off with a fruit rind, dumped on the beach. Not exactly its natural diet.

Boats are officially allowed to dispose of organic waste in the water if it’s more than ten miles offshore. But walking in the shallows of a popular turtle nesting beach on Isla Española revealed a very different story: the remains of limes, pineapple, watermelon rinds and a whole cabbage – plus a plastic spoon and red bag ties – littering the sand.

These foodstuffs were clearly dumped directly on the beach, and it poses a very important and rather worrying question: if one person is so willing to pollute the Galapagos, how many more are there?

There are now less animals but even more people – which precipitates a sense of anger when tourists don’t see something they’re expecting to. “Why aren’t there any penguins?” “Where are all the sharks?” “This is supposed to be THE place to swim with giant turtles and I haven’t seen a single one..”

It seems to make tourists more aggressively excited when they do see the animals they were hoping for. On San Cristobal, I watched in horror as a Spaniard snorkel above an elegant giant turtle and then reached down to stroke his shell. Only an hour later, the same man tripped and splashed in circles around a baby sealion in the shallows, snapping multiple photos with his GoPro, held mere centimetres from the confused animal’s face.

The visitors who come to the islands should be just that – visitors. They cannot and should not help or intervene when a heron pieces a baby iguana with its beak and flies away, or when a sealion wrestles an orange fish to death in its jaws. Because this is nature, in its most primal form – doing exactly what it wants to do, regardless of any outside opinion.

Animals dying is an integral part of nature’s process, and nowhere is this process more stark and evident. The problem with tourists helplessly viewing it here is that they romanticise the situation and feel responsible if a small bird doesn’t get enough water to drink.

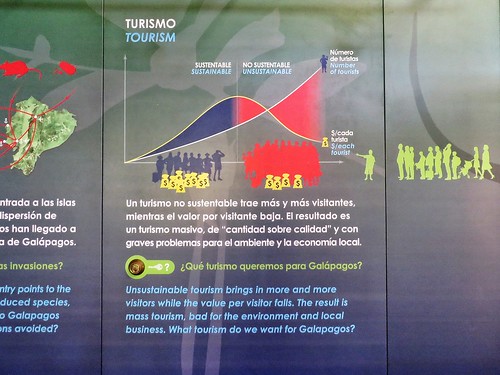

Should the Galapagos still welcome so much tourism?

A lot of people think that tourism shouldn’t exist on the islands – with good reason really. Despite pulling in a huge amount of revenue for Ecuador itself, and equally educating a number of people about how to protect and conserve the natural resources we have around the world, it seems somewhat at odds to then tramp all over the islands we’re attempting to protect, and snap photos and lie in the sand next to a number of different animals.

The islands are an incredible resource of information and a chance for many to see up close what they’ve spent years reading, researching, and dreaming about.

But then there’s the backpackers like me, who didn’t know much before arriving and just wanted to swim with sharks – or the Ecuadorian families, who simply want a nice beach and some strong sun to while away a long weekend. We’re pumping money into the Galapagos tourism industry, sure – but at what cost?

What’s so unique about these islands is the chance to watch the lives of so many wild creatures play out undisturbed.

But I don’t think it should matter if you see the array of “expected” animals in the Galapagos in order to call it a worthy trip. What does it gain, really? The islands are incredible even without ticking off a check list of creatures because their unique habitat is still just as unique, and just as suitable for them to flourish within.

Regardless of being captured on film.

A selection of the animals you can see in the Galapagos. If I hadn’t got these shots, would I feel like the islands had let me down?

Thankfully, the islands are almost exclusively reserved for wildlife nowadays, with only a few towns located in San Cristobal, Isabela and Santa Cruz.

But even these towns have expanded dramatically over the last fifty years – and who knows how much bigger they’ll get as tourism continues at its current rate?

Visiting the islands gives a sudden, uncomfortable realisation that, despite the good-intentioned resolutions of the environmentally conscious, the wildlife and landscapes of the Galapagos have existed this way for thousands of years, relatively untouched and unspoiled. It’s only with the introduction of humans into the mix that things have started to degenerate.

So should the Galapagos islands would benefit from a distinct lack of human invasion? Should the sun be setting on the cruise boat enterprises and the beach-loving holiday makers? After all, the islands have existed for thousands of years, and will continue to do so long after we’ve gone.

Maybe it’s time to start that process already.

Have you been to the Galapagos? Do you think there are too many tourists on the islands? Or do you think people deserve to see how unique they are?

19 Comments

Tracey

June 19, 2014 at 1:16 amThe sad truth is, without some kind of intervention, the destruction of the world’s beautiful places like the Galapagos will continue at an ever greater pace. Increasing world population, and the development of traditionally poorer nations leads to more tourists, more trampling, more damage.

I think we need globally protected areas where no humans are allowed so wildlife has a chance to prosper. Unfortunately, the areas that most need these sanctuaries are in developing nations; areas that already have many inhabitants. How do you tell people who are so poor they struggle to feed their families that they’re not allowed to hunt or fish anymore? To move them off the land they have called home for generations?

Flora

July 11, 2014 at 1:07 amIt’s a bit of a Sophie’s choice situation really, and your last point especially is really pertinent, Tracey. Often these places have remained pristine for so long because they’ve been protected by the locals – and to then block those same people from that land is simply abhorrent.

Zoe @ Tales from over the Horizon

June 19, 2014 at 1:52 amThank you for a well written post. It is always really important to respect the places you visit. There is a petrified stone forest in my homeland of New Zealand. The petrified tree stumps are a lot shorter now than they were because people kept on taking souvenirs. I was guilty of this at a different place as a child. On a volcanic island I took a small sulfur stone.

One never seems to be bad – after all it’s a big place. Unfortunately there are so many people doing the same thing.

Flora

July 11, 2014 at 1:05 amSadly if a thousand people take one tiny part of something, eventually the whole thing is destroyed. You’d think that photography would be sufficient as the modern form of souvenir taking now, but maybe it’s not…

Megan

June 19, 2014 at 3:36 amAlthough I’ve never been to the Galapagos, this is an issue I’ve been thinking about. It’s impossible to visit a place like this without making an impact of some degree. If me make too much of an impact, we risk ruining the place we want to visit. Sometimes I think it would be better for us to leave a place like the Galapagos alone and we can all enjoy knowing such a wonderful place exists, even if we can’t see it for ourselves. But in saying that, if I had the chance to visit, I’m pretty sure I would, which of course is hypocritical.

At the very least, each and every visitor to the Galapagos should be conscious of what effect they are having by being there. I hope your posts makes people more mindful of the issue.

Flora

July 11, 2014 at 1:09 amThat’s exactly the thing, Megan – I felt hypocritical enough writing this article after my second visit to the islands..! Maybe a sensible tactic would be to have much more of a mandatory eco-education for every visitor to the islands, so they leave being all too aware of what their visit has cost..

Kirsten (Kirst Over the World)

June 19, 2014 at 2:30 pmI’ve never been to the Galapagos, but always wanted to… it was the first place I remember I had the desire to visit as a kid, but I also worry about the impact of tourism.

It’s like when I rode an elephant in Bali – it made me really happy at the time. I love elephants, I wanted to be close and experience their majestic nature, the way they move, their texture, their playfulness. But now I look back and realise how badly elephants are treated, and I’m ashamed. Thing is, I wasn’t really aware at the time – I just wanted to see and touch this big animal, and the excitement overtook my ability to stand back, look at the big picture and question the animal’s life and treatment… just for MY wishes/tourism.

Coming to terms with the negative aspects of us/people just wanting to experience and see everything is a tough one. But maybe there are parts of the world we should just let nature have complete control over. It’s how the world is most beautiful anyway (through my eyes anyway!)

Flora

July 11, 2014 at 1:11 amI’ve done exactly the same Kirsten, and I’m not proud of it either – riding an elephant in Nepal because I was so enamoured with the idea, when I was sadly totally naive as to what I was partaking in. But that shame has made me more vocal about the plight of elephants within the tourism circuit, so I guess that’s one positive?!

Jo

June 19, 2014 at 3:19 pmHaving been to the Galapagos I totally appreciate the destruction we humans have and it’s often done unconsciously. As a race we are not good at co habitating and this is pretty evident all over the planet. In saying that I am so selfish that I want to go back and visit again, next time I hope to contribute by volunteering in some way.

Flora

July 11, 2014 at 1:12 amVery true, we’re inherently concerned with our welfare over that of other species, and it’s such a problem!

Nikki Sarimanolis

June 19, 2014 at 11:09 pmI visited the islands in 2007 but during the lower season months of may/June. There where very few tourists around but seeing how it’s becoming during high season isn’t nice but unfortunately not surprisingly. I have travelled a little and now live 6 months in uk and 6 in Thailand where I will soon live permanently. Over the past ten years I have seen many one quiet beautiful places getting over run and then ruined by tourists. The reasons we went to see them are fast disappearing not only in galapogos which is one of my most favorite and amazing places i’ve visited but it seems everywhere that is quiet beautiful and untouched soon becomes over run, disrespected and consequently ruined. Anyone who can benefit financially from this does so at any cost the the environment.

The island of koh Chang where I live in Thailand has rapidly changed from a calm beautiful place with the odd party to an arae of parties, drunken kids, rubbish and much dirtier seas. Koh tao or in English turtle island for example is full of dive schools yet after 20 dives there I didn’t see a single turtle and most often corals where dead trampled by trainee divers. Like an eary grave yard. To most who visit these places it’s still paradise but to those who knew them before.. All I can say is I hope this does not continue but sadly it will. The need to make money is a must for all of us but people do not understand that they are killing the initial attraction and so killing not only the planet but also in the long run their lively hoods!! Galapogos is an amazing place but sadly only one of many on the tourist hit list.

Katie @ The World on my Necklace

June 22, 2014 at 1:01 pmI haven’t been there yet, although I really want to go. It’s a hard one because you have to wonder, if they are closed off to tourists, will they actually be protected? Perhaps they should limit tourist numbers instead so that the Ecuadorian Government will still preserve these islands as they would still be making money from them. If the money dries up completely I am not convinced that the islands will stay protected.

Flora

July 11, 2014 at 1:19 amThat’s such a good point, Katie – I’ve no idea what the state of protection would be – because I’d assume that a vast amount of protecting the islands currently is so that tourists are kept happy with them. Plus, you know, UNESCO…

Steve | Live Smart Not Hard

July 15, 2014 at 1:30 amFlora just found your blog. Great stuff on the Galapagos. I’m looking at stopping there during a RTW jaunt. I’m also interested to hear more about your trip through Columbia.

Juergen

August 1, 2014 at 1:02 pmThe big question on a personal level is: what can you do?

Yes, you can stay away because otherwise you would be partaking in the tourist stampede, which threatens the paradise you wish to see. But it this really what you want? And anyhow: there’ll be probably 20 people eagerly lining up to take your place on the next boat.

You can of course chose the most responsible way to visit the islands and move around in this fragile environment. But again you are only a grain in the sand stream of tourists visiting every year.

I look at this problem quite often when travel blogging. Do I write about a “secret spot” we discovered, share it with our small readership and encourage others to go? Or do I skip all the “juicy bits” and write mostly about the “run of the mill” destinations?

We are overlanding in a camping vehicle, a few years ago we published the first English language GPS list of all our camping locations – many fellow travellers still use this list 5 years on. This time around I’m more selective and don’t publish places where I think it’s not appropriate (because the location has limited capacity, or requires a truly self-contained set-up so that people don’t leave any waste behind).

galextur

October 11, 2016 at 1:33 pmHey thank you for the amazing blog ! I have been to Galapagos and stayed in a hotel called Hotel Silberstein and they always tolled us to respect the nature when we did the tours and they also took care of the environment by recycling everything and so on. That is why I think it is okay to vivit the Galapagos Islands if you take care of the nature. I hope you keep writing such wonderfull blogs.

Flora

November 27, 2016 at 10:00 pmThanks for the recommendation!

Ann Block

November 1, 2016 at 8:45 pmThis is another great article about the Galapagos, Flora. I’m one of those people who always embarrasses my daughters by speaking up and telling other tourists NOT to feed the animals, NOT to walk in protected areas, etc. Did anyone ever confront that Spaniard? So hard to try to gently make people of the consequences of their misbehaviors…

Flora

November 27, 2016 at 9:23 pmUnfortunately I don’t think anyone confronted him… I know I should have, but it’s a little nerve-wracking to be on the spot like that 🙁 So glad you’re usually the voice of reason though, Anne!