At the top of Ceahlau mountain sits a little red house.

There is a garden just outside the front door, fenced in by a wooden gate, which looks out across a valley of Romanian mountains covered in trees.

In the house lives a radiologist. For seven days at a time, he spends his days shuffling from room to room, checking machines, writing notes, turning dials, tightening wires, and boiling kettles for cups of tea. Occasionally, he steps out into the garden in a pair of sandals to look out at the landscapes around him – often to watch the sun disappearing behind the mountain peaks.

But he is, for all intents and purposes, utterly alone.

To get to the little red house on Toaca Peak, the radiologist has to hike up the Ceahlau Massif – the most well-known mountain in the Carpathian mountain range, running through Neamt County in the eastern Moldavia region of Romania.

It’s a five hour route from his starting point in Durau. Once he’s entered the Ceahlau National Park, he quickly disappears into the chill of the forest: here, the late summer sun vanishes, eaten up by eager branches in greedy need of light.

Occasionally, a fallen tree blocks his path. The forest has been maintained by loggers for years: in the olden days, they would watch where the rain water drained then push the logs in the same directions.

On the way, he passes waterfalls surrounded by cold metal picnic benches; otherworldly boulders frozen in the midst of slanted pine trees; small painted flags on ancient trunks, denoting a route he may or may not choose to follow.

Other groups of hikers compete to keep pace with the radiologist, overtake him, then fall behind.

Clusters of eager tourists carrying plastic bags and trainers instead of backpacks and hiking boots wave hello, while stray dogs rush excitedly back and forth around their feet.

In four hours, the radiologist walks almost exclusively uphill. His journey takes him 1900m above sea level.

But unlike the hikers, who triumphantly end their journey at the Dochia cabin and are rewarded immediately with chilled glasses of local palinka, bowls of hot soup and loaves of fresh bread dipped in salt, the radiologist keeps on walking for another forty minutes towards the red house.

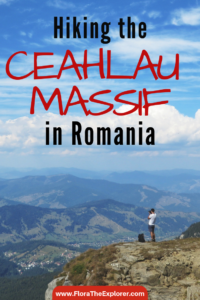

Hiking Romania’s Ceahlau Massif

Before arriving in Romania, I haven’t considered the prospect of a day spent climbing a mountain – but hiking in Romania is fantastically underrated.

Over 50% of the country is occupied by the Carpathian mountains, Europe’s second-longest mountain range, and there are thirty different natural and national parks in Romania with plenty of hiking routes and trails.

Because we’ve been exploring the Piatra Neamt area of Romania, it makes sense that my Romanian friends take us to Ceahlau Massif, a Romanian mountain so holy and which plays a role in so many ancient legends that it’s known as the ‘Romanian Olympus’.

While the five hour route from Durau to Toaca Peak is not for the faint-hearted, our group of hikers take it in our stride: stopping at the stunning Duruitoarea waterfall to eat our sandwiches, playing with local puppies at Cabana Fantanele, and conducting a lengthly photoshoot once we break through the trees and see the valley open out beneath us.

The last climb to sunset at Toaca Peak

There is a relentless wind blowing across the open spaces of Toaca Peak. The grass is bent double, and stones move seemingly of their own accord, scuttling down the oddly shaped rock formations that constitute the peak.

I look hopelessly at the path ahead of me. It’s only getting narrower – and by my calculations, much more treacherous.

After a day spent hiking up Ceahlau mountain, our group of Romanian bloggers have designated this peak as ‘the’ place to watch the sunset. From far off, it didn’t seem too impossible – even though I couldn’t see any kind of path from which to attack it.

But now, with my feet planted firmly on the rock’s sloping sides, I re-evaluate. This is going to be hard.

I have a few fears that often manifest when I’m travelling. Heights is a common one; so is the fear of falling. But the third is a specific amalgamation of the first two: a fear of being somewhere up high, in a narrow space, then losing my footing and falling.

Fears like these have the unique ability to disrupt a situation in a moment’s notice. Before I know it, the innocent journey to watch the sun setting from the top of Toaca Peak has transformed into a personal struggle. Am I going to face up to my rapidly growing worries? Or am I going to bail?

A few steps later, I’ve realised that the path is only growing more slippery and more narrow. Adding in the fear factor of having to make the later descent down the same steep gradient when it’s getting even darker, I make a decision.

I decide to turn around, and go back down

It’s not just giving up on reaching the uppermost height of Ceahlau that makes me feel ashamed. On my way down the path, I have to pass various members of my group, all of whom ask the same questions.

“Are you ok? Why are you going back?” Expressions of concern, offers to accompany me – like I’m suddenly an invalid. I mutter something about having vertigo and worrying constantly about falling. One man who I’ve never talked to before seems personally affected by my decision to stop the ascent.

“You can do it!” he urges. “We’ll help you – you’ve gone so far already – it’s beautiful up there and you can’t miss it!”

My faltering sense of balance grapples with the underlying guilt. Why do I feel so bad about not finishing a hike, anyway?

But once the others have vanished, I have the approaching sunset to myself.

The faint clouds above the valley are moving quickly in the wind; the rays of early evening light dramatically breaking through on an almost biblical scale. I realise I haven’t been truly alone so far on this trip, and I revel in the silence around me.

The radiologist and the corner flower

My back is to the little red house when I hear a voice. The radiologist clambers through the open front door, clutching at the glasses chain hanging around his neck. I don’t understand his Romanian words, nor the German he offers up next once he’s seen my confused face. Eventually we settle on broken English, and he invites me to step over the wooden fence, into the garden.

“There is a very rare flower in Romania,” he tells me, “and it is protected. It is called the corner flower. I have a few of them here.”

We are looking towards the soil for a flower I know I won’t recognise when a Romanian girl from our group walks past. She stops, looking confusedly at us both. She shares a few words with the radiologist, while I shrug my shoulders at her.

Soon, we are both crouching on a second modest patch of sloping earth, our cameras clicking incessantly, trying in vain to clearly capture the tiny silver-white flower as it moves in the wind. The Romanian girl has only seen the corner flower in books.

“How do you like Romania?” she says, not looking at me.

A silence. Then:

“It’s wild here…”

The wildness of this country has not made its full impact on me until this moment. I realise just how open and empty and raw it is up here; the soft colours of the sky above belying the whip of my hair against my cheek from the brutal wind.

On the pathway, the radiologist continues to speak at both of us. The girl translates his words, piecemeal.

“He says he measures radioactivity from up here… They were the first Romanian place to register the fallout from Chernobyl…”

“He says he spends a week here by himself before another radiologist changes places with him…”

“He says we should come to see the sunrise in the morning…”

Eventually, I spot a few other members of our group peering curiously over the fence at us. They are beckoned eagerly by the radiologist, and he asks if we’d like to go inside for some tea.

Inside the radiologist’s house

Unlike the trepidation I had immediately felt while climbing Toaca Peak, I see no problem with heading into the house. In fact, I’m eager to get a better idea of this man’s life.

He points out machines with indecipherable names, which hide in corners and hum in a low monotone. He stands awkwardly against a low table while we look appreciatively at different computers scattered around, and posters filled with diagrams that hang on the walls. A dried corner flower is stuck to his desk, beside a single pear on a metal plate.

In the next room, the radiologist gestures for us to sit at an old table covered in a plastic tablecloth with a print of breaded chicken dipper boxes while he busies himself in the kitchen. Eventually, he appears with plates of biscuits and three kinds of alcohol, a big grin on his face, and pours each of us a shot of ‘skinducu’, a homebrew with fresh gingseng hiding in the bottle.

It is pitch black outside when we stand to leave. The atmosphere in the room feels strangely charged, and when I pass the radiologist in the doorway, he squeezes my hip and invites us all to stay the night so we can see the sunset in the morning.

The wind is still howling around Toaca Peak. Half formed shapes blur in the hedgerows as we stumble along the path towards our cabin: two headtorches and the weak light of various mobile phones don’t do much to show us the way.

I’m still fascinated about the radiologist’s lonely life on the top of a mountain, and I pepper a friend with questions. Why does he need to live up here by himself? Did he tell us what he does to keep busy? What did he say about Chernobyl?

But his interest in the solitary man is waning; thinking ahead, instead, to the bright lights and groups of people at the cabin. He doesn’t have an answer to most of my questions, and eventually I hold my tongue.

Walking down from the top of the world

I don’t walk back to the radiologist’s house in time for sunrise. I don’t even see the dawn break from the comfort of the cabin; I am still wrapped in blankets and fast asleep.

We begin the mountain descent in a rush, hordes of Romanians still chewing cold pieces of toast and hurriedly threading their arms through backpack straps. The day is bright, the same clouds still moving quickly along the blue. A friend I walk alongside looks thoughtful and says,

“We are closer to the sky up here.”

Distance: 7.5km with an altitude difference of 995 metres

Time: 5 to 6 hours

Upward route:

– Durau to Cabana Fantanele: 1 hour

– Cabana Fantanele to Cabana Dochia: 2 hours

– Cabana Dochia to Toaca Peak: 30 mins

Downward route:

– Cabana Dochia to Duruitoarea Waterfall: 2 hours

– Duruitoarea Waterfall to Durau: 1.5 hours

Accommodation: the Fantanele chalet is at 1200 metres, while the Dochia chalet is at 1900 metres.

Weather: the entire route is accessible in summer, but in winter it’s only possible to walk as far as Duruitoarea waterfall.

19 Comments

Andra

November 5, 2014 at 2:19 pmDamn, how I miss this!

Flora

November 16, 2014 at 8:29 pmOhh me too my darling! I’ll come back as soon as I can 🙂

Nikita

November 5, 2014 at 7:38 pmThis is such a beautiful story. I kind of wish you’d had more time with him to ask all your questions. What an extraordinary life he must lead…

Flora

November 16, 2014 at 8:32 pmThanks so much Nikita! I wish I’d asked him more about his life – but then again, I think the situation was perhaps better the way it was. Staying as something of a mystery…

Kirstie

November 6, 2014 at 1:11 amI became completely enamored by Romania in the few days, I spent there, and I love hearing about this different side of the country. My NaNoWriMo also takes place in Romania (so far! not sure which direction I’m taking it!), so this provides some great writing inspiration.

Flora

November 16, 2014 at 8:36 pmAh how wonderful, Kirstie! I’m deep in the middle of NaNoWriMo too at the moment and I can only imagine how absorbed you must be in the world of Romania. If you haven’t already, do look at my other post about Romania for some more inspiration 🙂

Katie @ The World on my Necklace

November 7, 2014 at 4:06 amThis beautiful story makes me want to visit Romania even more. The hiking looks spectacular

Diana Southern

November 8, 2014 at 5:52 amThis is a beautiful story, Flora. Very thoughtful and both an easy and enjoyable read. I’m looking forward to reading more!

Flora

November 16, 2014 at 8:38 pmThanks so much Diana!

Laura

November 10, 2014 at 5:22 amSuch beautiful writing, Flora. Thanks for sharing this story. I love when I find those moments of peace and tranquility on a trip, sounds like you found it up there in Romania. I’m captivated by all of your stories of your time there.

Flora

November 16, 2014 at 8:40 pmThank you Laura – I”m so glad you enjoyed it! I really had an amazing time in Romania. It’s a country I never expected would captivate me quite so much!

bob

November 19, 2014 at 4:07 amYou are so cool Flora the explorer! When I finish school I hope to travel the whole world like you someday! But for now, please keep going!!!

Flora

December 9, 2014 at 3:03 pmThanks so much Bob!

Aggy

February 2, 2015 at 4:06 amAbsolutely love this piece. Romania is a special place, I lived there for 5 months to study and I hope to return back and discover more places. Your writings have really got my feet itch to return there as soon as possible!

Flora

February 9, 2015 at 8:42 pmAw, thanks so much Aggy 🙂 I’ve had a really wonderful couple of trips to Romania, and hopefully I’ll be back there again soon. Where were you studying?

Weekly Favorites | Alyson Sood

February 7, 2015 at 3:50 pm[…] idea of living alone at the top of the world is equally romantically appealing and […]

The Best Storytellers on the Internet - An American Abroad

March 4, 2015 at 3:55 pm[…] can’t help but to feel motivated to create my own once finishing with hers. Favorite Stories: The Romanian Radiologist who Lives at the Top of the World and A Lack of Familiarity: Learning how to […]

30 Things To Do In Romania Bucket List - Teacake Travels

January 1, 2019 at 8:26 pm[…] Ceahlau Massif is a beautiful mountain in the Piatra Neamt area of Romania. It’s one of the country’s most […]

Romania Travel Guide: 15 Amazing Things To Do | By Emilia Morariu

March 15, 2021 at 8:42 pm[…] Ceahlau Massif is located in the Eastern Carpathians division, more precisely in Neamt, a county of the Moldavia region. Ceahlau Massif is now a protected area and the park is known for beautiful landscapes with many rare and protected by law species of plants and animals. […]