In front of me stood four huge masked figures.

They towered upward, larger than life, their impassive faces staring down at me with vacantly fixed smiles.

The tiles creaked beneath my feet as I gazed at folds of bright crepe and silk material; the way trinkets hung motionless on belt buckles; flower petal headdresses lined with a thin layer of dust.

Nobody else was around me – and yet I could still feel dozens of pairs of empty eyes boring into my back from every side.

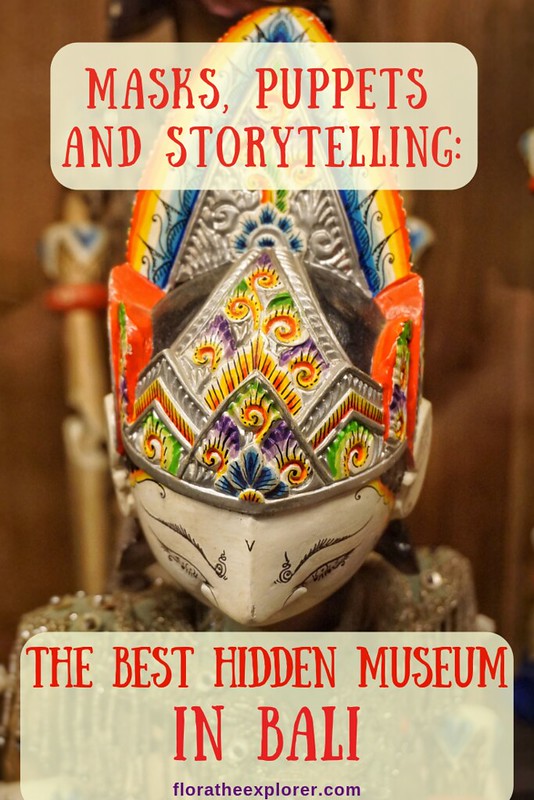

In my peripheral vision, I could see sequins and shining fabric, bright paint and gold thread. There were sharp teeth, curved beaks and open jaws all around as I stared up into these four faces, completely entranced.

Under this low wooden Indonesian roof, I’d somehow entered a completely different world.

I hadn’t even known we were coming here. My first hint was a mysterious smile from my boyfriend as I opened the car door; then he handed me his phone, pre-programmed with Google Map directions, and started driving.

It was our first foray into the chaos of Bali’s roads while driving our own hire car. My eyes were wide open, watching scooters whizzing past; huge extravagant sculptures at every roundabout; a highway lined with stone carvers busy in their workshops.

In fact, I was so distracted by the fact we were driving ourselves around an Indonesian island that I barely noticed when we pulled off-road onto a tiny path and up a steep ramp — and that’s when I realised where we were.

Setia Darma House of Mask and Puppets: a hidden corner of Indonesian culture

In 2004, an Indonesian man named Agustinus Prayitno reassembled five antique wooden joglo houses he’d brought over to Bali from Central and East Java. Concerned that the traditional Indonesian masks made by his ancestors were disappearing, Prayitno decided to establish a site where visitors could study and learn about the history of Indonesian culture. He filled these joglo houses with his private collection: a grand total of 1,300 puppets and 5,000 masks from all over the Indonesian archipelago and farther afield.

When I’d found a brief mention of Setia Darma House hidden away in our copy of the Bali Lonely Planet, I immediately knew I wanted to visit (because puppets and masks from around the world are, in my opinion, awesome) – but I’d been expecting it to be full of people.

Instead, we drove the car into an empty courtyard, dogs snapping at our tyres, and wandered down the steps past manicured hedges. The whole place appeared to be deserted, so we simply walked into the first wooden house we saw.

My lifelong fascination with masks and puppets

Coming from a theatrical family meant growing up with theatre paraphernalia all over the house. Alongside framed prints of famous English actors, costume designs and the posters from plays my parents appeared in, there was a pair of Indonesian wayang golek puppets hanging in our living room, bought by my mum during one of her acting tours in Jakarta, and a wall of masks from Greece, Japan and China in my dad’s study.

I used to be terrified of those masks as a child. If the study door was left open and I had to use the bathroom in the middle of the night, I would glance fearfully through the doorway and feel that delicious thread of anticipation trickle down my back.

What if they were watching me? What if they had moved?! More often than not, I would lie awake in bed willing my bladder to calm down so I didn’t need to get up.

But that fear has changed as I’ve grown older. It’s become a fascination as I’ve realised that all these faces are representative of something larger: that there are countless potential stories hiding behind each mask.

Their purpose is to tell stories: even though they can’t speak, they hold generations of myth, legend and history in their frozen expressions. Perhaps, due to my parents’ theatrical background, I always had an awareness of the potency behind these eerie faces.

Walking through the wooden joglo houses

From the moment we entered that first room in the first joglo house, I was hopelessly involved in the cultural objects laid out for us.

There were the faces of Hindu gods on black velvet; faces I recognised as Hanuman and Shiva. Bali is the only Hindu island in Indonesia, with around 83% of Balinese people adhering to Balinese Hinduism. For over a thousand years, the Balinese have used these masks in temple dances to perform epic stories from their Hindu religion like the Topeng dance and the Ramayana dance (the latter can be seen as part of the Kecak dance at Uluwatu, Bali).

The process is intensely spiritual. Balinese believe that the gods and goddesses are present in all things, which is true for a sacred mask too: it holds the life force of the character it represents. A Balinese dancer willingly embodies that spirit when he puts on the mask – they’re not just pretending to be someone else, like we would in the West, but they’re actually becoming that character.

(This video gives a great taster of what Balinese dancing is about!)

We walked into a room filled with Indonesian shadow puppets: their delicate silhouettes tracing the wall behind them like lace.

These flat articulated puppets, called wayang kulit, are made from thin sheets of perforated and carefully painted leather. Depending on the story being told, a set of wayang gulit puppets can comprise any number of characters: kings and princes, lovers and teachers, gods, demons and giants.

A single dalang puppet master moves the puppets and speaks for them to tell their stories, rear-projecting them onto a translucent screen which is pulled taut and lit with coconut oil lamps. Shadow puppet theatre performances take place at night – and they usually last until dawn, often accompanied by up to fifteen gamelan musicians.

We walked outside on our way to the next joglo house and ducked underneath a pavilion roof, only to see a man sitting quietly on the ground carving masks.

As he hammered and chipped carefully at the soft wood held between his feet, I realised there was another element to consider here: not just the mask wearers, and not just the characters they embody, but the people who make these masks in the first place, too.

Who are the Indonesian mask wearers?

By the time we’d reached the third house we’d attracted the attention of a guide; a lovely Balinese lady who stood at our elbows and flicked any light switches which didn’t turn on automatically.

I began to ask her questions about Setia Darma: how long had the house been open? What was the founder like? Had he collected all these masks himself, and how had he been able to convince so many people to hand over physical representations of their cultural history to him?

Walking through these buildings felt like witnessing the most intimate stories of the world’s communities, and I was fascinated by the idea that so many people had been involved in the process of getting these masks here. Moreover, they were all people who I’d never be able to see embodying these characters – which allowed my imagination to run wild.

I knew these masks would’ve been used in countless theatrical performances and to convey stories to captive audiences – but the more we saw, the more I became convinced that many of these masks would also be used for spiritual ceremonies; for shamanistic practices; for rituals in the dead of night beneath the full moon, up high on mountain tops or deep in dark forests – and probably for the most human of reasons.

Who knew how many of the masks I stood in front of had once been used for sending the spirits of the dead on their way; for inviting new life into pregnant women’s bodies; for exorcising bad spirits; for celebrating new rulers and condemning those who had wronged others?

How many unknown people have watched these colourful costumes whirling through the dark?

Things started to take a dark, eerie turn as we moved onward to the fourth house: twisted faces, jagged protrusions, eyeball-shaped lumps of wood worn smooth with the dirt of generations along their surface.

Some masks were held in cabinets with closed glass doors. Were they older and more valuable than the rest? Or was there another reason to stop us reaching out and touch them?

I imagined the hands of countless men and women picking up these masks, turning them over and over to inspect the craftsmanship, to touch-up the paint on open nostrils and wide eyes and full lips.

Some people say that because a mask is shaped like a living thing it’s able to maintain a connection to those who’ve worn it – or to continue carrying the energy of the spirit it represents.

Did these masks hold shadowy traces of their wearers? I could almost feel them behind me, standing just out of sight.

Why do we choose to mask ourselves?

At their base level, masks are about disguise. They can symbolise characters from history and myth, or they can intimidate enemies and show strength.

Masks can be physical and they can be symbolic. We all wear masks of different kinds; a collection of faces we present to the world when we want to be seen or received in different ways. But it doesn’t necessarily mean we become a different person.

After walking through five houses filled with cultural masks from around the world, I came away with the realisation that all cultures feel the intrinsic need to tell stories and perform rituals by assuming characters other than their own.

Agustinus Prayitno set up the Setia Darma House because he was concerned that masks and puppets are being lost to history, and younger generations of Indonesians are no longer interested in their past.

Prayinto, like other Balinese who dance with masks and operate puppets, is attempting to keep his culture alive by bringing it into the modern world – so much so that he’s even displayed a Barack Obama puppet standing with the puppet version of Prayitno himself.

The desire to mask ourselves is something we all share as humans. It connects us all.

At Setia Darma, Prayitno is attempting to preserve the heritage of Indonesian masks and puppets, and I, for one, sincerely hope he succeeds. A mask collection as big as this only solidifies our human need to change our identity, and to be seen differently from time to time.

Have you ever been to the house of masks and puppets? Do you have a hidden museum you’ve found on your travels & loved?

14 Comments

Ian McCurrach

November 30, 2018 at 11:46 pmA beautiful written piece and wonderfully atmospheric piece of writing! I loved the images you conjured up and the reference to you mum’s Indonesia puppets and lovely to be reminded of them as I was there when she bought them! Ian McCurrach XXX

Flora

November 30, 2018 at 11:58 pmOh my goodness Ian – were you really with her when she bought them?! That’s made me so happy! I wasn’t sure if she got them in Jakarta but I’m sure you can confirm whether that’s right 🙂 Here’s a link to what they look like on the back of the door: https://bit.ly/2P8RYSV

Barbie

December 1, 2018 at 12:10 pmI was there too Flora and in fact am trying to upload a pic of one that Sue gave me as a Birthday gift. Treasured x

Flora

December 2, 2018 at 12:42 amAww this is so lovely 😀 I can only imagine how many puppets she must’ve bought..!

Charlotte

December 1, 2018 at 12:42 amThis is so cool! I’ve been to Bali 9 times now but I’ve never heard about this place. I’m definitely adding it to my bucket list for my next visit 😀

Flora

December 1, 2018 at 6:50 pmWoah that’s amazing, Charlotte! It really doesn’t seem to be that well known, which really surprises me… but hopefully more people will discover it eventually!

lavieenmarine

December 1, 2018 at 11:34 amWow! This post is so amazing! I love the puppets and masks. The colors are incredible.

Flora

December 1, 2018 at 6:48 pmI’m glad you enjoyed it! They’re even more colourful to see in person 🙂

Ladies What Travel (@LadiesWTravel)

December 1, 2018 at 4:59 pmI find it sad like museums like this are so quiet, but I do love having places like this all to myself! We recently had that in a museum in the heart of Bangkok believe it or not, and I remember having the Devil Museum all to myself in Kaunas, Lithuania. It’s was such a quirky place, I loved it! #blogpostsaturday

Flora

December 1, 2018 at 6:52 pmHah, that’s a very good point Keri! I enjoy places like this even more when there’s nobody around and I can get totally absorbed in what I’m looking at 🙂 Also I can’t believe I missed out on the Devil Museum in Kaunas?!

Abhisek

December 3, 2018 at 8:17 amWhat a incredible post and article you write up! This looks epic in your post. Thank you so much for sharing this post.

Flora

December 4, 2018 at 2:46 pmThanks for reading Abhisek! I’m glad you enjoyed it 🙂

Pier

December 4, 2018 at 1:10 pmI’ve never been to Bali but I really felt really connected to your very well written story. My father was a set designer. I graduated in theatre studies and one of my favourite classes was about Balinese theatre and culture. Anecdotally, it was a shadow puppet show that made me love theatre, puppets and masks since I was a child.

It was fascinating to read about Setia Darma and the work of Mr. Agustinus Prayitno to preserve a fundemental expression of human culture.

geeta

December 5, 2018 at 6:45 amThanks for sharing this great article about some places & tips.. Loved this information and post.