In the summer of 2007 I travelled to Syria.

Our group were on a trip around the Middle East when we crossed over the Jordanian border to arrive in the ancient walled city of Damascus. A collection of women from England, Australia, Canada and the US, we walked past palm trees and half ruined architecture above multi-coloured parasols.

My eyes were constantly pulled towards every tiny detail of this bizarre and bustling city. To bare lightbulbs strung into strips of stainless steel roofing; electric wires snaking across the brickwork; tiny birds tweeting from the inside of intricately carved cages.

At the entrance to the city’s Al-Hamidiyah Souq – famous for its pistachio-rolled ice cream cones at the Bakdash parlour – we passed under a huge billboard with Bashar al-Assad’s grinning face and pointing finger saying ‘I Believe in Syria’.

The cramped stores inside were stuffed to the gills: shelves of carved wooden boxes and little glass bottles of perfume jostling for space between cellophane wrapped bars of olive oil soap, piles of sticky sweets and old ticking clocks.

Rows of shisha pipes hung like colourful dormant snakes alongside delicately strung lutes with bent bridges and frilly white children’s dresses. Displays of women’s headscarves were tied around the heads of obliging female busts made from white plastic in a far-off factory somewhere.

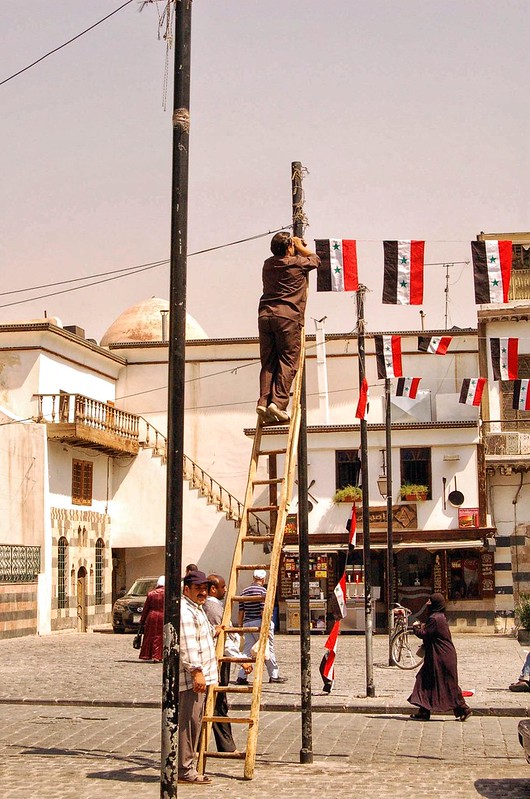

In a sunny paved courtyard, I watched a man balanced on a wooden ladder as he tied knots in a string of Syrian flags. Groups of people flocked to the entrance of a mosque; the women shapeless in their black coverings, the men in light slacks and loose white shirts with sleeves raised to the elbows.

The Umayyad Mosque, one of the largest and oldest in the world, had strict entrance instructions: in through a side door if we were all foreigners and all women. A duo of impassive men at the front entrance indicated that we should don grey hooded smocks sealed with velcro patches.

The white marble looked golden in the bright sunlight, and we walked quickly because the surface radiated heat and we were obligatorily barefoot. Gilded paintings were painstakingly etched into the marble above the heads of the elderly women who sat cross-legged in rows or formed circular groups against the cool internal walls.

So what do I think about Syria now?

Four years later when bombs began to fall over Syria, I looked through my collection of photos and couldn’t believe how quickly things could change. My diary noted the memory of just how often we saw Bashar’s face: grinning unperturbed from fridge magnets, his portrait propped inside small windows, plastered on towering billboards and across the painted surface of car windscreen protectors.

Yet that was the only indication for me, a tourist, of what was going to happen to Syria. The majority of my memories were the beginnings of stories I briefly caught sight of – in the souks, on the streets, and from the windows of buses.

There was the immovable figure in a tight red teeshirt and slick hair, exuding his own sense of magnetism beside a blackcurrant juice stall in a sun-drenched market corner, a huge metal bowl of the berries balanced artfully above a camouflaged box of ice.

There was the man proudly peeling vegetables before a captive circular audience on a busy street – the first person to ever alert me to the concept of spiralising a courgette.

Like most countries I travel to (and usually because I’m actively searching for it), I felt a tenuous connection to this country which I’d barely touched the surface of but still vaguely knew.

Throughout our week in Syria I hungrily breathed in the dusty heat, the bright sparks of colour, the twisting lanes, the sudden expanse of desert after cities crammed full of activity.

And let’s not forget all that overwhelming history.

But things are different now. When I tell people I’ve been to Syria, they’re usually shocked. It’s like they can’t remember it before – as if the hundreds of years of dusty bazaars, fruit juice sellers, and old men napping in the sunlight barely ever happened.

But then it’s likely they never had a significant concept of Syria before the war began.

Perspective is elastic: it can shift and change.

It breaks me every time I realise that the perspective of ‘Syria’ and ‘Syrians’ for so many millions is fundamentally based on death, destruction and desperate refugees.

Somehow, that perspective seems to help in distancing many people from the Syrians who up until a decade ago were a normal nation of people: they owned cars and houses, worked normal jobs and lived normal, modern Middle Eastern lives – until suddenly they didn’t.

So what exactly am I getting at?

Since volunteering in the Calais refugee camps with people from Syria and many other countries, I’ve been thinking a lot about how easy it is for outside influences to form our perceptions. More importantly, about how these perceptions are then sustained because many of us often don’t re-address them.

Unless we have a reason to. Unless there’s an outside jolt to the system which changes our perception for us.

Take Calais, for instance.

When I was a teenager, my parents got into the habit of doing the ‘Calais wine run’: catching the Eurotunnel train over to the coast of France every six months to pick up cheap wine and beer. I spent most of these trips sitting grumpily in the back seat of our family car, asserting my newfound sense of independence by ignoring my mum’s Carrefour shopping list and heading into the rest of the attached shopping centre to lust over the French selections at H&M.

Simply put, this French city on the water has always meant very little to me except as the location of a large supermarket, a few restaurants which served a fantastic lunchtime helping of moule frites, and somewhere with positive memories for my family.

In the first few days of 2016, nearly a decade since I’d first been to Calais, I leaned forward in my friend Beth’s car to stare at street names through a rain spotted windscreen.

“Is it that way to the warehouse?”

Drenched in bad weather and the bleary skies of early morning, the Calais harbour nonetheless still looked exactly how I remembered. The bridge to the main square, the lighthouse, the ferries in the distance: all shockingly familiar. I couldn’t quite believe it was the same city where I’d been focused on clothes shopping – a world away from helping to provide refugees with waterproofs to withstand the incessant rain.

Over the next week of volunteering, my perception of Calais was repeatedly reshaped. Amongst all the information I frenziedly absorbed about border control policies, immigration law and the potted histories of various war-torn countries, I also learned a chilling fact about Calais itself.

Unbeknownst to me, the ‘Calais Jungle’ had actually existed in some way or another – most notably as the ‘Sangatte’ camp – for at least fifteen years. Mere metres away from the restaurants and supermarkets I’d frequented throughout my bored teenage life.

It was chilling because it meant I’d clearly never researched Calais beyond what the outside world had told me. My parents had their own political opinions but I wasn’t exactly a news-aware teen: I’d felt no desire to educate myself about global happenings that weren’t directly pushed my way.

Now I look at photos from those Calais trips which Mum took happily from the passenger seat of my dad’s car. I’ll never know if she was aware of the refugees living in squalor nearby.

Seeing the same place in a different way

Because of that week in Syria I now have a handful of ‘before’ images, both mental and photographical, to combat those showing the country’s destruction all over the news.

I still feel uneasy about publishing photographs from pre-war Syria. I know it could easily be taken the wrong way – like utilising an abhorrent situation for the sake of blog traffic – and if you think that’s what I’m doing then I wholeheartedly apologise. But that is absolutely not my intention.

To forget what Syria used to be like is to insult the millions who have called the country home: the millions who have died and been displaced as a result of a civil war that still rages on. And it’s also illustrative of a lack of faith that things will eventually change.

How much can a country change in a few years?

In 1991, one of my closest friends escaped with her family from Bosnia & Herzegovina during the Yugoslav Wars. They lived with nuns in Italy for a while until they found more permanent homes: her cousins and aunt in the United States, my friend and her mum in London. She was three years old.

Last summer I stood in a church in the centre of Dubrovnik, Croatia, and watched her get married. The same city that in my lifetime and hers was besieged for over a year has now become one of Europe’s hottest tourist destinations – and I’d hazard a guess that lots of those tourists in their mid-twenties or younger don’t remember much about the Yugoslav Wars, either.

People’s memories are malleable by default. It’s probably a good thing, particularly when tourist dollars contribute hugely to rebuilding infrastructures of countries affected by earthquakes and tsunamis, wars and political unrest.

Places change. They recover. While I’d never naively say “Syria will probably get better eventually!” with zero expertise on the topic, history does show us that civil wars end, citizens pick themselves up, and slowly the localised world tries to get back to a semblance of its former, normal self.

I hope against hope that this is something on the horizon for Syria and its people.

While writing this article, I had to check the differences between perspective and perception – and in my research I found this article, which ends with the following:

“Putting oneself in another’s perspective changes our perception of life. It is the perception of our reality that governs the perspective towards our life. The question where do our perspectives come from? In fact, they come from our perceptions.”

“We break our perceptions to make our perspectives.”

I think we could all do well to stick with this idea.

24 Comments

Ally Fiesta (@AllyFiesta)

February 25, 2016 at 2:00 pmI’ve was in Ecuador in August during a major strike but in no major city for two weeks. I saw the news reports but I was safe but I did have to skip Quito due to the unrest. That was incredibly sad because I would have liked to spend a week there.

Flora

February 27, 2016 at 11:23 amIt’s a shame you never made it to Quito, Ally – hopefully you’ll get to visit again 🙂

Kara Freedman

February 25, 2016 at 3:22 pmBeautifully written post. I’ve often thought about this issue of the other side of places – the one that you don’t see or don’t hear about for one reason or another. I think that may be what people talk about when they want to get off the beaten path, but you’ve taken the idea to a much more meaningful and important place. Who are the people around us that we don’t notice? The places just a few steps further that we’ll never visit? And what is the impact of not knowing about them, never learning more?

Flora

February 27, 2016 at 4:25 pmMy hope is for more people around the world to see Syrians and refugees of other nationalities as their counterparts – communities with history, pride and integrity – instead of a section of society to be ‘pitied’ or looked down on. Just because most will probably never visit Syria now doesn’t mean the country or its people deserve to be forgotten.

Andrea Anastasiou

February 25, 2016 at 4:49 pmFlora, this blog post gave me goosebumps. I, too, travelled to Damascus back in 2008, and whenever I tell people I’ve been to Syria I’m met with the same expressions of disbelief, like they cannot remember Syria ever being anything but war-torn.

Damascus had such a lasting impression on me; I found the city to be one of the most magical cities in the world and I always vowed to return. I sometimes look through my own photo albums from the trip to remind myself of what it looked like before it was turned into the ruined place that we see in the news reports.

It saddens me to think of all the millions of lives that have been devastated as a result of the war and how quickly the country has been turned to rubble. It makes me grateful for my own security, and it also makes me aware of how quickly things can change, both from good to bad and from bad back to good. It’s why I try not to take anything in my life for granted.

I hope that you’re right and that we’ll see Syria get back on its feet in our lifetime.

Thanks for the thought-provoking post.

Flora

February 27, 2016 at 4:31 pmThanks for giving your perspective of Syria too, Andrea – and your kind words 🙂 It’s so humbling to have to take lessons in being grateful for your circumstances as a result of what’s happening in the Middle East – but if that’s the way that incites a mass belief in change, so be it.

Susanne

February 25, 2016 at 6:22 pmWhat a thought provoking article and has certainly made me think about my own perceptions of places. It was fascinating to hear of your experience in Syria and I really enjoyed your photos.

The great thing about travel is its ability to change our perceptions and give us perspective,

Thanks for a great read, Susanne:-)

Flora

February 27, 2016 at 4:31 pmThanks so much for reading, Susanne – I’m glad the article provided you with some food for thought 🙂

Eve

February 25, 2016 at 7:45 pmHi Flora, it’s an important topic you touch. I also visited Syria – it was early March 2011, a few weeks before the first demonstrations began. I feel lucky to have seen the Ummayad mosque while it was still safe.

On a less important note, just for the sake of clarity – I believe the 13th photo (with the ruins) and the one with playing men are from Jordan, not from Syria. The ruins are in Jerash close to the border with Syria

Flora

February 27, 2016 at 4:17 pmThanks for the clarification, Eve – I should’ve checked before I published! – but you’re right, the ruins are indeed from Jerash.

veena lives her life.

February 26, 2016 at 12:24 pmFlora, this is a great article a great reminder of Syria’s history before the current events began unfolding. Thanks for sharing! xx

Flora

February 27, 2016 at 4:35 pmThanks so much for reading, Veena!

wayfarover

February 26, 2016 at 2:36 pmThis is an absolutely brilliant post and you do well linking Eastern Europe to the situation you’re talking about. Could put Southeast Asia up on that list, too. I hope no one takes you posting pictures of Syria in the wrong way, I know I didn’t, instead it was really interesting to see the before-pictures and it makes the current situation all the sadder. When the war finally ends, Syria will be in ruins, but I am confident that it will still get better, as naive as it might be to think that. Obviously it’s going to take a long time, but wars shift focus and they move to other places, so maybe Syria still has hope.

Flora

February 27, 2016 at 4:45 pmNobody has said anything in that vein, but a long time ago when I posted photos of pre-war Syria on the site I had something of a negative backlash. I’d still love to believe the same – that ruined Syria will still have a chance to get better when/if the war ever ends.

Candice

February 26, 2016 at 6:42 pmHow lucky you are to have seen Syria before it all fell apart. Perspective is elastic, indeed.

Flora

February 27, 2016 at 4:42 pmYep – although it’s a strange type of luck.

GadAbouttheGlobe

February 29, 2016 at 1:49 amI’ve never been to Syria or a war-torn country, but I served in Madagascar in the Peace Corps and I was evacuated when they had their political coup in 2009. It’s a strange mix of feelings when you’re pulled from a country and you leave friends behind. It was a huge reminder to me of the privilege I have in this world. Even though I was living there and volunteering, I could leave at a moments notice when it became dangerous. There are so many people who don’t have that same luxury. Great post on how these harsh realities can affect a traveler’s perception.

Flora

March 12, 2016 at 1:43 pmI can’t imagine how surreal it must have felt to be unwillingly pulled out of a country in sudden turmoil – but you’re right, it must make you both humble and grateful. Not to mention giving a whole new perspective to see the world through. Thanks so much for reading, and sharing your story too!

Kristine

March 3, 2016 at 3:42 amWow, the sharp changes Syria went through because of war. Thank you for sharing the before pictures! Syria looks so beautiful and full of life, which makes it even sadder now. It reminds again that everything is fragile and things can change drastically within a very short period of time.

Flora

March 12, 2016 at 1:49 pmIt really was such a stunning and detailed country – even if I only saw it for a week…

Julia

March 25, 2016 at 4:50 pmSuch a thought-provoking piece. Living in Turkey a few years back, there was a lot of talk (mostly negative) about Syrian refugees. As you said, it is important to look beyond the recent events and re-evaluate the perceptions that are often created by mass media. Thank you for sharing!

Travel Blog Tips: The Travel Tester Favourite Reads March 2016

June 17, 2016 at 10:36 pm[…] From Syria to Calais: Nine Years of Changing Perspectives [Syria] Flora The Explorer […]

Ray

November 5, 2016 at 10:30 pmMy friend first got me interested in visiting Syria in 2010. It seemed intriguing because it had been stable for nearly a decade like you said and was even making many Top 10 travel lists, including that of Lonely Planet. However, I decided to buy a condo in mid-2010, so Syria had to wait. Now it will have to wait indefinitely until this war is over.

Thanks for sharing these photos of Syria before the war. And you are right. If the former Yugoslav Republic can eventually pick up the pieces and be open for tourism again nearly 20 years later, who’s to say that the same won’t happen to Syria, Iraq or Libya? Just hoping peace and stability comes to this part of the world sooner rather than later!

Flora

November 27, 2016 at 9:00 pmI’m hoping against hope that a resolution to the fighting and massacres can be found soon.. Syria was such a beautiful country with such a rich history and culture – but regardless of its former self, it’s still horrific that a population can be decimated in this way 🙁