I was nervous.

Standing awkwardly on a patch of sloping mud below a grassy sand dune, I stared down at my hefty walking boots half covered by waterproof trousers. Opposite me stood dozens of men in a quiet line, many of their faces turned to me with vague interest.

I had no idea what I was supposed to do.

A few dozen metres away, a heavy crane machine picked up identical shipping containers, stacking them up like shiny white Jenga blocks. Separating us from the building work was a metal chain link fence hung with fraying jumpers and pairs of sodden jeans. My eyes were caught repeatedly by the ragged tops of thin tents, their entrance ways flapping in the breeze.

I couldn’t shake the bizarreness of the situation. Of all the countries I’ve travelled through, there haven’t been many moments where I’ve stood in near silence with two Eritreans, three men from Sudan, a number of Syrians and a group of Egyptian teenagers, all watching a young boy from Iraq steadfastly pushing a bike through the slick, clumped mud.

I felt completely out of my depth – and with good reason.

A word about refugee camps

Ask most people living a comfortable life in the Western world if they’ve been inside a refugee camp, and the answer will likely be no.

It’s not surprising: however many remote places someone chooses to travel to, the parts of the world populated by transient refugees are still far away from the tourist track. Like Dadaab in Kenya, Zaatari in Jordan, and Jabalia in the Gaza Strip, the biggest refugee camps are relatively close to places globally regarded as dangerous, usually because they’re embroiled in civil war or political unrest, run by dictators or violent militia groups.

As someone who regularly volunteers when travelling, I’m embarrassed to admit that working in refugee camps has never been something I’ve really considered – but there’s a good reason. I don’t have any discernible skills beyond a desire to help, and a quick Google search will tell you that sprawling camps filled with tens of thousands of refugees need professional aid by governments, the United Nations, or charitable bodies like the Red Cross: people who are trained to know what they’re doing.

In the past, it feels like refugee camps haven’t exactly been a central issue in the general public consciousness unless we’ve actively engaged with the topic. But something strange is happening in the world right now. Those camps in those far off countries are getting closer – and so are the refugees who populate them.

What do you do when the refugee camps come right up to your doorstep?

Welcome to ‘The Jungle’

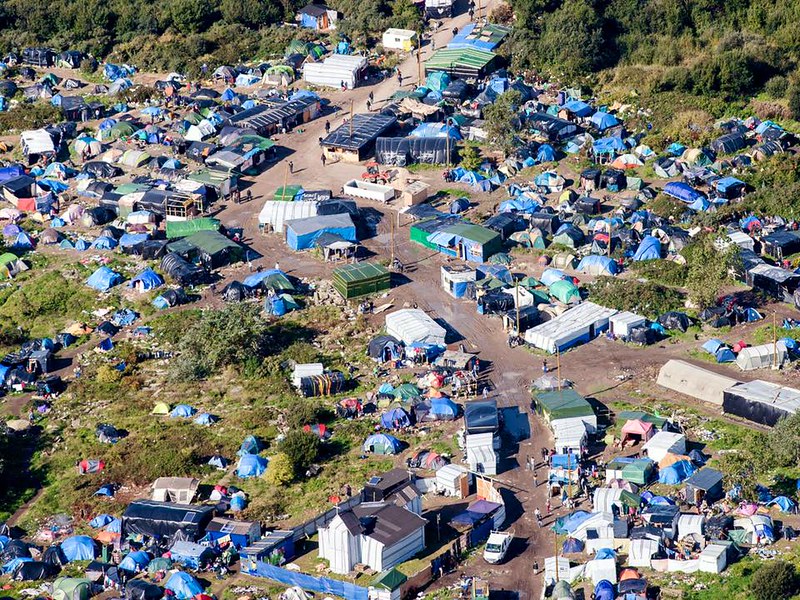

Right now, in a muddy French industrial dumping ground twenty one miles away from the coast of England, there’s a refugee camp populated by about nine thousand people from all over the world. Some of them have spent months, if not years, making their way here from Sudan, Iraq, Eritrea, Syria, Afghanistan and a dozen other war torn countries. They are hoping to finally reach a place of safety where they can reunite with loved ones, claim asylum and start their lives again.

For many, this intended destination is England – but their way into the UK is blocked by a body of water, a multi million pound white steel fence topped with razor wire, and the constant presence of French police kitted out in full riot gear: black plastic shoulder pads, huge guns hanging at their waist.

Life in the camp is dire. People are crowded into thin tents and makeshift shelters in the freezing mud, with poor sanitation and little to occupy their thoughts beyond how they might eventually escape. Despite different nationalities living involuntarily alongside each other, the main source of tension in camp actually comes from the rows of police vans that cluster around the camp’s main entrance and sit along the highway above the tents.

The French police are there to prevent refugees from breaching the EuroTunnel or boarding a ferry in an attempt to smuggle themselves over the border. At night they throw tear gas into camp, while groups of far-right activists join in by throwing lit fireworks.

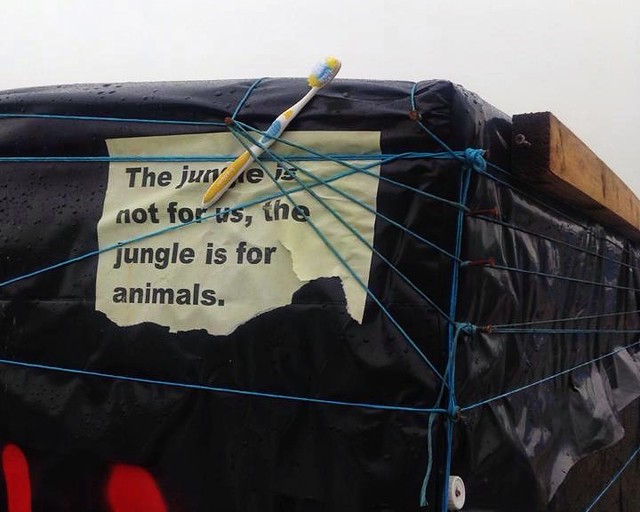

People feel trapped. Like the French government are treating them like animals.

The camp known as the ‘Calais Jungle’ is a disaster zone. Despite growing larger by the day, nobody is officially in charge: France has not yet recognised the area as an official ‘refugee camp,’ meaning the UNHCR (the UN’s Refugee Agency) are unable to offer aid or assistance.

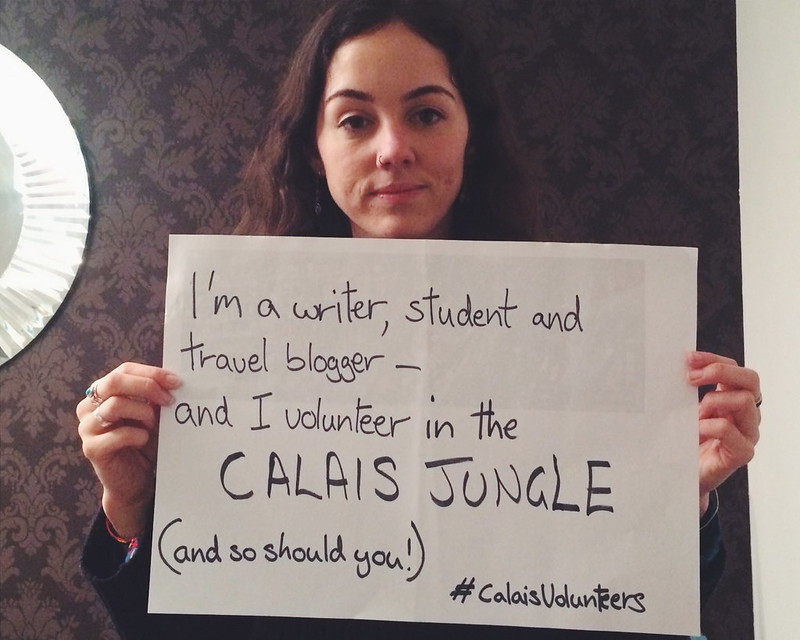

Instead, the responsibility of providing food, clothing, shelter and support has fallen chiefly to the efforts of grassroots volunteer groups, comprised of individual people who feel compelled to help simply because they can’t believe this humanitarian crisis is happening in a wealthy corner of western Europe.

Joining the volunteer effort in Calais

I caught my first glimpse of the Calais camp through the police-patrolled fence, driving along the highway. We were on route to our first day at the donations warehouse with a carload of fellow volunteers, and I had no real clue what to expect from the week ahead. Most pressing on my mind was the idea of stepping inside the camp as a poverty tourist – something I simply couldn’t stand.

It was really difficult to explain my motivation: from a writer’s perspective I felt it was crucial to see the camp’s conditions with my own eyes, but I couldn’t get rid of another underlying terror. Did I just want to see how awful it was? Was it the same as rubbernecking a car crash on the side of the road?

I ended up vowing to myself that I’d only venture inside the camp if I was actually needed – and for my first three days in Calais I worked flat out at the warehouse, packing boxes with a passion that bordered on delirium.

Eventually I was asked to help with a day of clothing distributions in camp. By that point I’d spoken to enough volunteers about their experiences with camp life, but I still had strange assumptions about what the place would be like.

Many articles I’ve read convey the camp’s atmosphere as being dramatic and scary, and I was half expecting a sudden shift in temperature or an unmistakeable sense that ‘This Place Was Different’ – but my first impressions were simple.

Mud, tents, rubbish, and people.

I’d left my hi-vis vest back at the warehouse, tied my hair back, put on baggy waterproof trousers over my jeans: after months of speaking with ‘the elders’ (various community leaders living in the camp), long-term volunteers have decided it’s more respectful to the refugees if female visitors cover up.

Image: Tamar Longmuir

We trudged along the camp’s main roadway (still thick with mud, but flattened down due to repeated tyre treads and countless footsteps) towards a little wooden hut where one of the warehouse vans was waiting. Thanks to a widely disseminated schedule of the various donations offered by volunteers each day, most of the men already waiting at the distribution point knew we only had boxes of waterproof jackets with us.

My sole job was to keep an eye on the queue as it snaked through the mud while chatting to people, ensuring that any minor scuffles about queue jumping or general impatience were quelled before they began.

Except nothing problematic happened.

A few people asked me what was being distributed: “coats… for the water,” I said, miming raindrops falling. I joked with a guy from Iraq about putting his wooden shelter on wheels. A group of guys laughingly placed a red glittery hat with earflaps onto another volunteer’s head, then wouldn’t let her give it back to them. Two men wanted to know whether we were currently standing in France or in England. Dozens of us watched in wonder as a man called to a black crow perched on the roof of a caravan, who dutifully hopped down onto the man’s waiting finger.

I watched a little girl giggling as she hurtled around on a pink bike, complete with mud-caked stabilisers. Behind her came a little boy on a scooter who I assumed was her brother.

Surreal setting aside, the whole process felt very normal. Like any other queue in the world.

A further exploration of camp life

Details became clearer as the day went on and we moved to a second distribution point for the afternoon, walking through camp to reach it.

That meant passing all the places I’d heard about: the faded pink Welcome Caravan where new arrivals are led for immediate access to some warm clothes and a sleeping bag; the Ashram Kitchen, staffed by volunteers and serving up meals to hundreds of refugees daily; the Jungle Books library; the Christian Orthodox church.

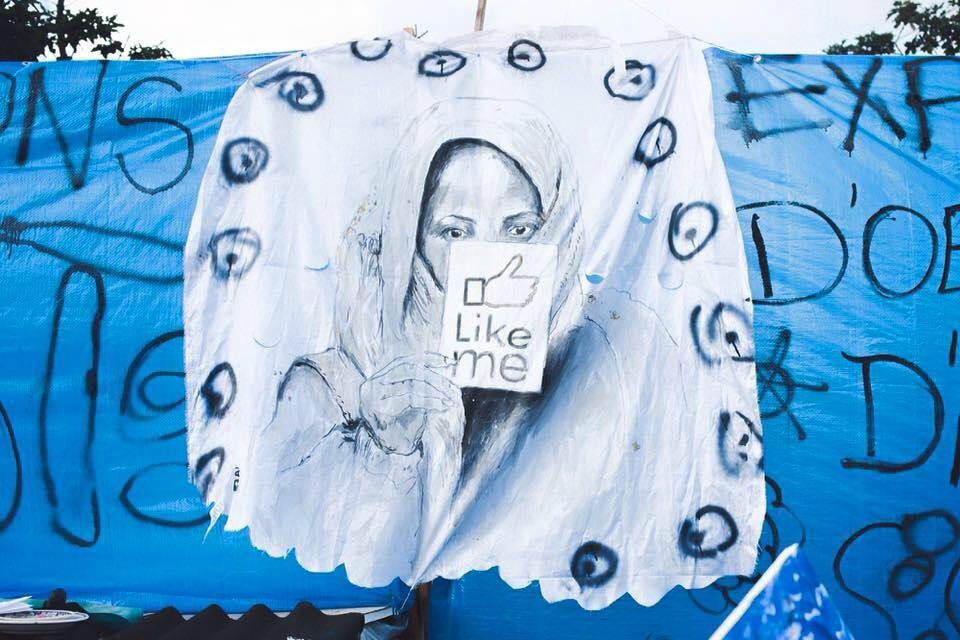

I kept seeing pieces of art painted onto shelter walls and hung from the sides of tents: simple slogans about Cameron, his UK government, and freedom, love and peace.

Men wandered past in flipflops with bare feet, greeting each other with two kisses on each cheek. Men with their socks tucked into their trousers clustered outside the doorways of little shacks (which I soon realised were restaurants when the scent of frying garlic wafted past us).

Although many people seemed engaged in activity, there was still a level of despondency. The amount of rubbish trodden into the ground and spiked onto bushes was extraordinary; so was the worrying number of broken tents and swathes of mud.

By the time we’d reached our second distribution point I’d begun to fully absorb the dire situation these people were in, and as we stepped gingerly around a huge stagnant puddle of water to reach a second line of queuing men, I realised I was terrified of engaging someone in conversation and having nothing positive to say.

So I stood awkwardly in the sand for two hours as men shuffled along in the queue. My small talk was minimal at best: I wanted to magically make everyone’s situations better, and felt hopeless at my own inadequacy. I fervently wished I had the vaguest understanding of Arabic so I could at least try to chat in a language some might find more familiar.

Once the coats had all been given out and the queue had dispersed, a well respected man from the nearby Sudanese community invited us into his shelter for tea. I followed the other volunteers, taking off my boots and crawling into a small space filled with layered blankets and pillows on the raised floor and stapled to the walls.

Image: Claire Pemberton-James

For the next hour we warmed our bodies and our minds with hot sweet tea sipped from little plastic cups while our Sudanese friend laid out packets of nuts and menthol sweets. We settled into easy conversation with him about opinions of England and what the refugees know about UK asylum laws until a volunteer friend reappeared with the van and we left camp for the day, my mind still reeling with opposing ideas of what I’d seen and felt.

A new day in camp – and a new perspective

A few days later, I headed back to the camp again – this time in beautiful sunshine and accompanied by five other English girls. We had rolls of bin bags stuffed in our coat pockets and gloves on our hands, and for the next few hours we cleared up rubbish.

Unlike on my last visit, I felt like I was actually doing something of value in camp. Together, we picked up sodden clothes and broken boots; food wrappers and drinks cans; empty polystyrene boxes and plastic spoons from the community kitchens.

We debated about moving objects that might have alternative uses: old saucepans near to homemade fire grates and somewhat damp bedding outside of tents were often left alone.

Perhaps due to the unexpectedly good weather, there was a constant feeling of activity around us.

Vans moved slowly along the central thoroughfare and indicated for us to throw our full bin bags into the back; men from Médecins du Monde in white took photos in an effort to map the camp’s layout; a bulldozer laid down scatterings of gravel for a new pathway; teams of volunteers put together the walls of shelters they’d already part-constructed back in the warehouse.

The demoralising aspect of litter picking was realising just how little difference we were making in the grand scheme of the camp’s cleanliness, and it nagged at me until one of the girls I was with unknowingly voiced the perfect rebuttal. That although putting shards of plastic cups into bin bags for a few hours might not look like much, there’s something more impacting about us repeatedly showing our concern for the welfare of the refugees living in camp.

Simply by being there, and being willing to help.

Just before we left, I stood outside the Christian Orthodox church beside a man from Eritrea. He was waiting to go in for a service, the day after Orthodox Christmas, so I quickly asked him if it was alright to take a photo. “Of course!” he said, pointing to the tree covered with fake snow and giving me a thumbs up.

The church is one of the camp’s most well known structures: located in the centre off the main street, near a distribution point and a strip of water spigots where people come to wash their faces and clean their teeth. The mud gets thick and waterlogged around this area but the church itself has a modicum of privacy, thanks to a white tarp fence built around it.

And despite being in the midst of a muddy field, people still come from all over the camp to pray. To be in a place where they can quietly reflect.

So what are my takeaways from Calais refugee camp?

Although I have nothing to compare it to, the Calais camp is unlike anything I’ve seen before. There are wildly different cultures, nationalities and languages squeezed alongside each other; deplorable conditions that people consistently put on a brave face to confront; tireless and passionate workers striving to change situations that, by rights, shouldn’t be theirs to fix.

I didn’t feel aggression from the refugees. I didn’t feel scared. More than anything, I felt inspired. Everywhere I looked, I saw unparalleled levels of support; the sharing of skills and resources; how far a little bit of collective effort can go.

The question that heads this article – ‘why come to the Calais camps?’ – is a pertinent one. This camp isn’t an otherworldly situation anymore. This is right in the middle of our sightlines, sitting squarely on top of our normal, relatively comfortable lives. The problem isn’t going away. As long as we have wars and disorder, we will have refugees. We can’t shy away from it.

It’s good that I was nervous to come to Calais. This is not a situation that anyone should be able to take lightly. My incentives for volunteering were to see, to help and to learn. I feel sick when I think how little I knew about the millions of displaced people in the world – and how little I still know – but at least I’ve begun the process of educating myself.

So why should you come to Calais? It’s simple. Until you’ve seen what’s really going on, how can you really know what your opinion is?

Have you worked in a refugee camp before? Are you planning to volunteer in Calais?

All images in this article are mine, unless otherwise stated. No faces of volunteers or refugees have been revealed without their prior permission.

Volunteering

If you’re considering volunteering in Calais (or anywhere else related to the refugee crisis), you have my complete support! It’s really so easy to head to Calais if you’re based in the UK – simply decide what date you’ll arrive & let the guys at CalAidipedia know. As a grassroots charity with no funding, they can’t provide transport or accommodation but if you have a few days spare I guarantee you’ll meet some fantastic people & help to make a difference.

20 Comments

Gerry pare

January 21, 2016 at 3:07 pmThank you for the education.

Flora

January 22, 2016 at 10:38 amThank you so much for reading, Gerry!

nikitaeatonlusignan

January 21, 2016 at 7:45 pmThanks for writing this! I would love to volunteer in a refugee camp… Or maybe “love” is the wrong word, but I feel like it’s something I need to see. Good for you for helping out. It’s disgusting that human beings have to live in those conditions, but I’m sure meeting people who care does a lot for them.

Flora

January 23, 2016 at 11:28 pmI know what you mean, Nikita – it’s a pretty strange feeling when you’ve actively got the desire to work in a place that’s so sad. But equally I think it’s essential to act if you feel compelled to – and then talk about the experience with as many people as possible <3

Gina

January 22, 2016 at 6:04 amSuch a great article, I too volunteer when traveling. I’ve been watching about these camps on the news for the past few weeks and now I’ve read this it gives me inspiration to look into volunteering there when I go to Europe in June.

And Good one you for doing something towards these troubles. 😄

Flora

January 24, 2016 at 12:11 amI’m so glad to hear you volunteer when you’re travelling as well, Gina! It’s an incredibly eye opening experience – if you have the opportunity to spend some time volunteering at the Calais camps then I highly recommend it.

Rachel

January 22, 2016 at 7:22 pmWow. Such a great article. Thank you for sharing and for introducing me to the phrase “poverty tourism.” It’s easy to forget that people do have to live like this and it makes it even more cringeworthy when people fight against refugees seeking refuge in “their country” as often times, refugees are living in degrading conditions!

Flora

January 24, 2016 at 12:34 amThanks so much for reading, Rachel 🙂 Sadly poverty tourism is something that does happen (usually when people are a little too keen on seeing how ‘the other half’ live), but while it’s difficult to handle it’s equally important to help others see why refugees need help from those of us in safer places.

Natalie

January 23, 2016 at 12:55 amThank you for sharing. I have volunteered with refugees locally and donated financially when possible. I think this is such an important cause and I truly appreciate you sharing your experience.

Flora

January 24, 2016 at 12:47 amWonderful to hear it, Natalie 🙂

Zita Ingster

January 23, 2016 at 4:43 pmBLESS you for caring and doing and telling about it! it is intellectually + emotionally distressful to watch and intolerable to accept such human misery and disinterest from those who could help , Shame on France and UK. i You are first blogger to report this There are many horror camps to visit with women and children in the cold , snow.and mud in Hungary, Serbia, Greece ! Shame on these places !

I want to tell you about a NEW FREE mobile calls app named VSIM to make LD calls ,save on roaming costs, get local numbers and pay local costs, and call anyone anywhere or be called and save money Works in WIFI. FREE calls, texts, photo sharing between same app users , Download is free on googleplay and apple store. for android and iphones

Spread the word to those who NEED to stay in touch and NEED to save on calling families so far away ! Thanks and cheers! Your kindness will come back to you tenfold .

Zita in Budapest .

.

Flora

January 24, 2016 at 1:05 amThank you for the info about the VSIM app Zita! I’ll have to look into it, sounds like it could be a useful resource for volunteers & refugees alike. Have you told any other volunteer groups about it?

Sophie Davis

January 23, 2016 at 5:51 pmGreat article Flora!

Flora

January 24, 2016 at 12:48 amThanks Sophie!

Foreign Loren

January 25, 2016 at 7:50 amThanks for sharing your story from Calais! I spent 10 days earlier this winter volunteering on the Greek Island of Lesvos where asylum seekers are arriving daily from Turkey (with most people originally from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan). It was interesting to hear how similar much of your work was to mine despite the distance. People arrived to Greece so hopeful for what is to come but, unfortunately, they face so many hurdles on the way to finding a better life for themselves and their families. However, I found it inspiring that volunteers from all over the world had come for the sole purpose of helping those in need.

Katie Featherstone

January 25, 2016 at 12:22 pmThanks for this, it was interesting to read how you found it. We’re hoping to go in March too. It’s easy to feel helpless about the whole situation, but I suppose we can only try.

Best Travel Blogs 2016 Award | by Volunteer World

March 10, 2016 at 11:37 pm[…] Flora started to write about her adventures in 2012 and has been passionate about inspiring others with her travel and volunteering experiences ever since. We think it’s awesome how she combines exploring the world with social commitment. Check out her new section about volunteering at the refugee camps in Calais. […]

Rosa Yoo

December 21, 2016 at 7:57 amThis is just whole kit of information that I shoulda known. I live in Korea, Seoul and want to help out refugees out there. I’ve sent dm on instagram so check it out!

Helpful Ways to Volunteer with the Homeless in London

December 17, 2019 at 1:41 pm[…] if you’re sofa-surfing; if you’re escaping a problematic or abusive relationship; if you’re a refugee. In fact, at this […]

butterflyrascal

March 30, 2023 at 7:46 amThank you Flora, I can tell the situation in the jungle has never been better than how you describe it now. Usually there are no restaurants, only broken shelters and police corps who destroy everything anyone tried to build there, ever. Time to head there again, I’m located elsewhere in Belgium right now, but the people in the camp are very dear to me.